Beyond the Fields We Know

‘Whatever I write, I start with the setting . . . ‘

How and why a writer can be inspired by a landscape or location by Marian L Thorpe, author of the Empire’s Legacy Trilogy.

One of my favourite walks is along part of a long-distance path that follows the route of a Roman road that probably follows an even older track. At its North Sea end, wooden henges stood. On either side of the section I walk most frequently, Bronze Age barrows rise from the fields. The ruins of Roman villas lie under the soil not far from it; the moot hill of the Saxon hundred it crosses is believed to be by its side. In The King of Elfland’s Daughter, Lord Dunsany described fairyland as lying ‘beyond the fields we know.’ I don’t write about fairyland, but I do write about a world that lies lightly on a palimpsest of our real, historic world.

Whatever I write, I start with the setting. Stories emerge from landscapes for me, and even when they are complete fiction their settings are strongly based on a real place. Whether it’s verse—the first work I had accepted for publication as an adult—or my short stories, or my novels, they are all rooted in and inseparable from the physical world in which they are set.

I had a rural childhood of the sort almost unimaginable today. I grew up over 50 years ago, roaming fields and woods and lanes on foot or on my bike, often alone. I watched the progression of wildflowers over the summer; I watched planting and harvest.

I had a rural childhood of the sort almost unimaginable today. I grew up over 50 years ago, roaming fields and woods and lanes on foot or on my bike, often alone. I watched the progression of wildflowers over the summer; I watched planting and harvest.

I learned to identify trees and birds and wildlife, and understand to some extent the landscape in which I lived and the forces, human and natural, that had shaped it. The theme of the first novel I ever began, at seventeen, is the relationship between a man and the land, the deep, hard-fought and hard-won connection between the two—and that’s still a theme in my Empire’s Legacy series.

The books I loved to read as a child were books that were firmly placed in their landscapes. Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons series; The Wind in the Willows. Puck of Pook’s Hill. Rosemary Sutcliffe, and many, many more. Books where landscape is a character, in a way. I also grew up in a family where history was important. It was discussed, my interest encouraged. My father’s love was Tudor/Plantagenet history; mine evolved into late classical/early medieval.

In my twenties and thirties my husband and I travelled as extensively as we could, not to cities but to the footpaths and trails of almost every country and county of the UK and throughout North America. I soaked up landscape, I soaked up history, and I fell deeply in love with the concept of landscape history. (Thanks, Time Team!) So when I began to write Empire’s Daughter, the first book in the Empire’s Legacy series, I started with a landscape: the coast of Anglesey. I saw it, and then I began to populate it with characters and a society.

The series isn’t set in the real world, but neither is it truly a fantasy world. There are no variations from the laws of physics or nature, only (barely) a fantasy geography. There are no fae or otherworldly creatures, only the flora and fauna of northern and central Europe.

The series isn’t set in the real world, but neither is it truly a fantasy world. There are no variations from the laws of physics or nature, only (barely) a fantasy geography. There are no fae or otherworldly creatures, only the flora and fauna of northern and central Europe.

Every place in the entire series has a real-life inspiration, and I’ve been to most of them. (If I haven’t, I’ve substituted a place I have been, in a similar ecological/geographic niche.)

The reasons for this are many, and varied. As someone who was, for a chunk of her life, a biological scientist, and has been for all her life an amateur field naturalist, I am annoyed beyond words with unreal worlds whose ecologies don’t work. So that’s one reason, but not the major one. The books are set in an analogue world, but it’s one that for many people will be both recognizable and familiar—and that was done on purpose. Because my books explore questions of societal and socio-sexual structures and expectations, because they are more concerned with questions of philosophy and morality and politics than battles, I didn’t want to add another layer of worldbuilding to the mix. It would have been a distraction, another thing for the reader to have to think about and absorb.

In the first two books my main character Lena never leaves the known world, one based entirely on the UK both geographically and historically. There’s a Wall, there’s a country north of the Wall, and these two countries are long-term enemies. The country north of the Wall has a province that sometimes belongs to them, and sometimes to the seafaring people from even further north. Even the battles are based on real ones: Stanford Bridge, the Battle of Maldon. For me, and for anyone who learned British history in any detail, this all should feel familiar – and that’s what I wanted: to place, in a familiar setting, a story that challenges a number of societal structures.

The third reason for the settings of my books is simple: I draw heavily on my own experiences in the descriptions of my characters’ interactions with their environments. I’ve been pelted by hailstones on a mountainside. I’ve slipped on scree; I’ve walked on dusty, arid plains, climbed up waterfalls (not quite as terrifying as the one Lena does), camped in the cold and wet and lived (albeit briefly) in primitive wooden huts. It’s easier to write about real experiences than it is to make them up.

Mix the idea of a world that lies beyond the fields we know, add the discovered and undiscovered history that lies beneath the fields we know, throw in a strong seasoning of love for landscape and nature, a dash of the belief that we are shaped by the places we love, and bake that all in the mind of a writer—and you have the genesis of the world I created in Empire’s Legacy. © Marian L Thorpe 2023

Find out more about Marian L Thorpe’s books on: marianlthorpe.com

Many generations past, the great empire from the east left Lena’s country to its own defences. Now invasion threatens…and to save their land, women must learn the skills of war.

Many generations past, the great empire from the east left Lena’s country to its own defences. Now invasion threatens…and to save their land, women must learn the skills of war.

But in a world reminiscent of Britain after the fall of Rome, only men fight; women farm and fish. Lena’s choice to answer her leader’s call to arms separates her from her lover Maya, beginning her journey of exploration: a journey of body, mind and heart.

Read my review of Empire’s Daughter on Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/54687565-empire-s-daughter

Find Marian’s books on: https://books2read.com/marianlthorpe

From my desk here in the Province of Málaga I can see the Sierra de Las Nieves. This was where the Moors of Al-Ándalus used to harvest snow to be collected in summer for sherbet and to keep medicines cool. To the right out of a large picture window is the bandalero country of The Empress Emerald; to the left, beyond mauve-shaded mountains, are ancient fishing villages now known as the Costa del Sol, but once prey to the Barbary corsairs featured in The Chosen Man Trilogy.

From my desk here in the Province of Málaga I can see the Sierra de Las Nieves. This was where the Moors of Al-Ándalus used to harvest snow to be collected in summer for sherbet and to keep medicines cool. To the right out of a large picture window is the bandalero country of The Empress Emerald; to the left, beyond mauve-shaded mountains, are ancient fishing villages now known as the Costa del Sol, but once prey to the Barbary corsairs featured in The Chosen Man Trilogy.

Despite my somewhat Latinized outlook, though, what I see through my Spanish picture window when I am at my desk in Málaga is still with a realistic Englishwoman’s eyes.

Despite my somewhat Latinized outlook, though, what I see through my Spanish picture window when I am at my desk in Málaga is still with a realistic Englishwoman’s eyes. If, like me, you enjoy novels that takes you into the past and/or far away, check out the excellent Bristish historical fiction author, Deborah Swift. She has a new novel set in 17th century Italy out now, too.

If, like me, you enjoy novels that takes you into the past and/or far away, check out the excellent Bristish historical fiction author, Deborah Swift. She has a new novel set in 17th century Italy out now, too. If you enjoy gritty, contemporary British police crime fiction, try B.A. Morton’s frightening, heart-rending ‘Crime on the Tyne’.

If you enjoy gritty, contemporary British police crime fiction, try B.A. Morton’s frightening, heart-rending ‘Crime on the Tyne’.

In Britain and Ireland, there was the added, critical risk of imminent invasion. It had happened in Poland and the Channel Islands, it could happen in Britain. The detail about the German U-boat surfacing off the Cornish coast to take on fresh water in Local Resistance was taken from a German sailor’s account. I didn’t invent that.

In Britain and Ireland, there was the added, critical risk of imminent invasion. It had happened in Poland and the Channel Islands, it could happen in Britain. The detail about the German U-boat surfacing off the Cornish coast to take on fresh water in Local Resistance was taken from a German sailor’s account. I didn’t invent that. How a Cornish fishing village uses its ancient smuggling tradition to evade rationing while preparing to defend their country when ‘Jerry’ landed forms the background to Local Resistance; how people as diverse as Land Army girls and cosmopolitan actors coped three years into the war underlies the shenanigans and criminal activities in Private Lives.

How a Cornish fishing village uses its ancient smuggling tradition to evade rationing while preparing to defend their country when ‘Jerry’ landed forms the background to Local Resistance; how people as diverse as Land Army girls and cosmopolitan actors coped three years into the war underlies the shenanigans and criminal activities in Private Lives.

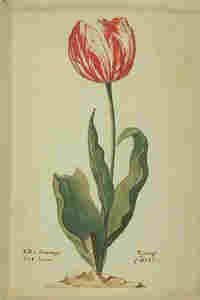

The first Ludo story was inspired by a combination of two events; one very real with devastating financial consequences, the other un-real, other-worldly, when I ‘saw’ people during a visit to Cotehele in Cornwall (while preparing for another book altogether). Cotehele, a National Trust property on the River Tamar, became the fictional house Crimphele, then the story-line fell into place as I watched news coverage of the Lehman Brothers and mortgage scandals in the USA. I had lived in the Netherlands, was acquainted with the tulip bubble, and it seemed quite plausible that a character such as Ludo (the infamous ancestor of Leo Kazan in The Empress Emerald) might be employed as an agent provocateur acting for Habsburg Spain and, supposedly, for Rome. After fitting these elements together, I then had to learn some hard facts behind ‘tulip mania’ and some of the vaguer, barely credible history behind Vatican espionage and secret agents. It took a good two years to write The Chosen Man, fortunately reviews show it was all worthwhile.

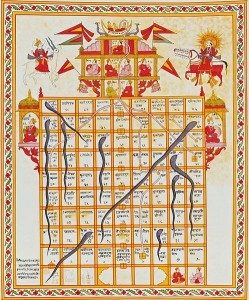

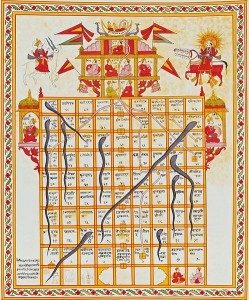

The first Ludo story was inspired by a combination of two events; one very real with devastating financial consequences, the other un-real, other-worldly, when I ‘saw’ people during a visit to Cotehele in Cornwall (while preparing for another book altogether). Cotehele, a National Trust property on the River Tamar, became the fictional house Crimphele, then the story-line fell into place as I watched news coverage of the Lehman Brothers and mortgage scandals in the USA. I had lived in the Netherlands, was acquainted with the tulip bubble, and it seemed quite plausible that a character such as Ludo (the infamous ancestor of Leo Kazan in The Empress Emerald) might be employed as an agent provocateur acting for Habsburg Spain and, supposedly, for Rome. After fitting these elements together, I then had to learn some hard facts behind ‘tulip mania’ and some of the vaguer, barely credible history behind Vatican espionage and secret agents. It took a good two years to write The Chosen Man, fortunately reviews show it was all worthwhile. A long, long time ago I had a gap year job in a jewellery and antique shop, it wasn’t what I wanted to do for the rest of my life, but I learnt a lot and it helped greatly while preparing notes for A Turning Wind. During my research, I came across the writing of the French merchant-explorer Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (1605-1689). In a spell-binding account of how diamonds were mined in the Golconda region of India, Tavernier quotes an account supposedly written by Marco Polo of how diamonds were found and traded in the area centuries before. It was too good not to use so I wove it into the opening scene. That, and the ancient ethical origins of the game Snakes and Ladders, created the background for Ludo’s second adventure, via documented history on Portugal and the ambitious Duchess of Braganza, and a little known, unrealized treaty between Charles 1st and Felipe IV of Spain. Having spent many years living near El Escorial, the scenes set there with the infamous Conde-Duque de Olivares and Velazquez were easy to write.

A long, long time ago I had a gap year job in a jewellery and antique shop, it wasn’t what I wanted to do for the rest of my life, but I learnt a lot and it helped greatly while preparing notes for A Turning Wind. During my research, I came across the writing of the French merchant-explorer Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (1605-1689). In a spell-binding account of how diamonds were mined in the Golconda region of India, Tavernier quotes an account supposedly written by Marco Polo of how diamonds were found and traded in the area centuries before. It was too good not to use so I wove it into the opening scene. That, and the ancient ethical origins of the game Snakes and Ladders, created the background for Ludo’s second adventure, via documented history on Portugal and the ambitious Duchess of Braganza, and a little known, unrealized treaty between Charles 1st and Felipe IV of Spain. Having spent many years living near El Escorial, the scenes set there with the infamous Conde-Duque de Olivares and Velazquez were easy to write. One of my aims while writing this trilogy was to show how decisions made in high places can have appalling consequences for ordinary members of society. This story in particular shows how one’s personal destiny can be determined by events far beyond one’s control. The over-riding circumstance here is a civil war. What happens to Ludo, Alina and Marcos is determined by a conflict not of their making in a country not their own and their efforts to safeguard their families. Regrettably, it is something many readers can relate to nowadays.

One of my aims while writing this trilogy was to show how decisions made in high places can have appalling consequences for ordinary members of society. This story in particular shows how one’s personal destiny can be determined by events far beyond one’s control. The over-riding circumstance here is a civil war. What happens to Ludo, Alina and Marcos is determined by a conflict not of their making in a country not their own and their efforts to safeguard their families. Regrettably, it is something many readers can relate to nowadays. This final story takes Ludo back to Portovenere in Liguria, Italy – a place I have visited many times. The name derives from a temple dedicated to the goddess Venus; and there’s a Doria castle there too. Agustin, the Doria Doge of Genoa of the epoch, had a daughter, she is un-named in the Doria family tree but she may have lived there. Barbary corsairs constantly raided the Ligurian coast – so again, what if . . .?

This final story takes Ludo back to Portovenere in Liguria, Italy – a place I have visited many times. The name derives from a temple dedicated to the goddess Venus; and there’s a Doria castle there too. Agustin, the Doria Doge of Genoa of the epoch, had a daughter, she is un-named in the Doria family tree but she may have lived there. Barbary corsairs constantly raided the Ligurian coast – so again, what if . . .?

I self-published the first title, Warhorn – Sons of Iberia, in 2013 and the fourth will be available in the Spring of 2019. The series is set during the 2nd Punic War which was fought between Carthage and Rome between 218BC and 202BC.

I self-published the first title, Warhorn – Sons of Iberia, in 2013 and the fourth will be available in the Spring of 2019. The series is set during the 2nd Punic War which was fought between Carthage and Rome between 218BC and 202BC. While the ancient people of Iberia are long gone, their land remains largely unchanged and just as dramatic. The river Tagus which flows a thousand kilometers across Spain and Portugal to the Atlantic from its wellspring in the Fuente de García. The wild coast of the Costa Brava. The moon-like Bardenas Reales. Interesting local settings are vital in creating depth and atmosphere in any tale and from the beautiful blue coastal waters of the Mediterranean to the high mountains of the Pyrenees, Iberia offers a palette of landscapes in which countless deeds of heroism wait to unfold.

While the ancient people of Iberia are long gone, their land remains largely unchanged and just as dramatic. The river Tagus which flows a thousand kilometers across Spain and Portugal to the Atlantic from its wellspring in the Fuente de García. The wild coast of the Costa Brava. The moon-like Bardenas Reales. Interesting local settings are vital in creating depth and atmosphere in any tale and from the beautiful blue coastal waters of the Mediterranean to the high mountains of the Pyrenees, Iberia offers a palette of landscapes in which countless deeds of heroism wait to unfold. Other wonderful creatures that still roam the wilds of Iberia include the endangered Iberian lynx, brown bear, and Spanish Ibex. The Iberian lynx often features in Sons of Iberia and I begin the series through the eyes of a lynx.

Other wonderful creatures that still roam the wilds of Iberia include the endangered Iberian lynx, brown bear, and Spanish Ibex. The Iberian lynx often features in Sons of Iberia and I begin the series through the eyes of a lynx. Glenn Bauer – Sources and links:

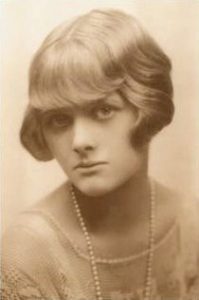

Glenn Bauer – Sources and links: It is 80 years now since Daphne du Maurier’s novel Rebecca was first released. Back in 1938, du Maurier’s publishers were nervous about the novel’s future, but the story has become a classic: a world-wide favourite, a play, a television series, even an iconic black and white movie. For a while, back in the 90s, new editions of du Maurier’s novels were hard to obtain, but with the recent film version of My Cousin Rachel she is very much back in the public eye.

It is 80 years now since Daphne du Maurier’s novel Rebecca was first released. Back in 1938, du Maurier’s publishers were nervous about the novel’s future, but the story has become a classic: a world-wide favourite, a play, a television series, even an iconic black and white movie. For a while, back in the 90s, new editions of du Maurier’s novels were hard to obtain, but with the recent film version of My Cousin Rachel she is very much back in the public eye. Big houses, full of private tragedies and secret histories, feature in many of her novels. Looking at photographs of Menabilly I wonder if that house stands as a metaphor for her fiction – as full of conflicting emotions, versions of the past and fantasies as the house on the strand. Such thoughts and ideas are only suggested, it is up to each reader to interpret them of course, and as in real life we interpret them according to our own way of thinking and personal experiences. Readers bring their own baggage to any book.

Big houses, full of private tragedies and secret histories, feature in many of her novels. Looking at photographs of Menabilly I wonder if that house stands as a metaphor for her fiction – as full of conflicting emotions, versions of the past and fantasies as the house on the strand. Such thoughts and ideas are only suggested, it is up to each reader to interpret them of course, and as in real life we interpret them according to our own way of thinking and personal experiences. Readers bring their own baggage to any book. This post first appeared in the Discovering Diamonds blog:

This post first appeared in the Discovering Diamonds blog:  Healthy, well-trained horses entered in modern long-distance races, sometimes called endurance races (for a very good reason) can cover up to 100 miles in a day. The favoured breed is the Arabian, but while the type of breed matters, it’s the training that is important. Each mount has to be prepared for these distances over a long period of time, and this includes getting used to eating hard fodder at different times of the day, which many horses do not or will not do.

Healthy, well-trained horses entered in modern long-distance races, sometimes called endurance races (for a very good reason) can cover up to 100 miles in a day. The favoured breed is the Arabian, but while the type of breed matters, it’s the training that is important. Each mount has to be prepared for these distances over a long period of time, and this includes getting used to eating hard fodder at different times of the day, which many horses do not or will not do. A final word: these blog posts are written from my personal experience of a life-time caring for and training horses. If you go to other on-line sources you may find conflicting or differing information.

A final word: these blog posts are written from my personal experience of a life-time caring for and training horses. If you go to other on-line sources you may find conflicting or differing information. The sheik was seated on cushions in a high-ceilinged room. There were no intricate tiles such as those of the Arab homes Ludo knew in North Africa, only brightly coloured wall-hangings and mats, and on a low oblong table a large patchwork cloth.

The sheik was seated on cushions in a high-ceilinged room. There were no intricate tiles such as those of the Arab homes Ludo knew in North Africa, only brightly coloured wall-hangings and mats, and on a low oblong table a large patchwork cloth.