The setting for Roma Nova

by Alison Morton

Imagining Roma Nova – Or is it real?

Ever since I read Violet Needham’s Stormy Petrel series as a child I’ve been caught by the idea of imaginary countries in Central Europe. Needham’s books for children invoke a romantic ‘otherwhere’, making it familiar, with a subtle, understated magical tone. Possibly seeming old-fashioned now, she’s very much the unsung, and sadly unknown, mother of modern fantasy with a mix of heroism, sacrifice and honour. At first her books were deemed by (grown-up) publishers to be too complex for children, but the story goes that one of the children of a family director at William Collins publishers loved the story, so it was accepted for publication. Talk about serendipity!

A little older, I was entranced by The Prisoner of Zenda and its sequel Rupert of Hentzau – classic examples of ‘Central Europe’. I thirsted after everything I could find about this amorphous region with no defined boundaries but a definite idea of itself. The Austro-Hungarian Empire seemed to be a concrete representation, but it wasn’t quite. When I learnt German, I found many ideas and writings about Mitteleuropa as a concept. As an adult, I found The Radetzky March by Joseph Roth to be a sweeping history of heroism and duty, desire and compromise, tragedy and heartbreak, a story over generations that lasts until the eve of the First World War. But that empire was vast, diverse and autocratic. Like the Ancient Roman Empire, it collapsed under its own weight and the pressure of people’s desire for their own homeland and self-governance, whether by conquest or democracy.

With all that in mind, my even greater obsession with all 1,229 years of Ancient Rome and a reasonably good knowledge of the alpine regions, I dreamt about an ideal place for the setting for my Romans seeking a new home. But it would be a small colonia, not an empire! It had to be fertile enough to sustain people, defendable and off the beaten track. So I started researching…

Imagine my delight when I found in real history that at the dusk of the Western Roman Empire people had actually established safe places in the mountains called Fliehburgen. A number of these successfully protected their population during the barbarian invasions, sometimes developing into permanent settlements for decades in the most dangerous periods. And for the Roma Novans, this became necessary in the years after the story in EXSILIUM.

Over their history, the Roma Novans, cultivated their land, built their cities, suffered invasion, rebuilt their cities, extended their holdings, negotiated treaties and managed to survive into the 21st century when the first modern Roma Nova adventure takes place in INCEPTIO.

What does Roma Nova look like in the 21st century?

It’s an alpine country with lower lying valleys a few small towns (Castra Lucilla to the south of the main city, Brancadorum at the east, Aquae Caesaris to the west) and a river city full of columns, a forum, Senate house and temples. High mountains and hills to three sides, although very useful for defence in past ages, keep the 21st century pilots from Air Roma Nova (and most international airlines) on their toes when landing their passenger aircraft after a long haul flight!

Sadly, you can’t use Google Maps to view Roma Nova’s geography from space nor load a Wikipedia page for its history. But inventing a country doesn’t mean you can throw any old facts into your book. They have to hang together. Geography is very important as you need to know what crops they can grow – spelt, oats, olives in sheltered areas, vines, vegetables and fruit – and what animals they raise – cows, sheep, horses, pigs, poultry, etc.

To look back to when those first Roman dissidents left Italy in AD 395 and trekked north to found Roma Nova, I also needed to deepen my specific knowledge about Roman life and culture at that time: their mindset, their customs, their concerns, their ways of doing things. As a reference, the first chapters of Christopher Wickham’s book The Inheritance of Rome draws a clear and detailed picture.

With the Roma Nova books, I’ve used terms that people might already know like the Roman sword, gladius, greeting such as salve, solidi as money, ranks like legate and centurion. But I’ve made the gladius carbon steel, the solidi have currency notes, debit cards and apps as well as coins, and I’ve mixed in other European military ranks such as captain in with traditional Roman ranks. It gives a sense of history that’s gone forward and adapted to the modern age.

Ancient Romans were fabulous engineers and technologists, organised and determined to apply practical solutions to the needs of their complex and demanding civilisation, so I’ve positioned them in the 21st century at the forefront of the communications and digital revolutions.

The silver mines in Roma Nova’s mountains and the resulting processing industry that underpinned Roma Nova’s early economy, and still play an extremely important role in 21st century Roma Nova, are another allusion to ancient Rome. Silver was a big reason the Romans wanted Britannia. Dacia (Romania) and Noricum (Austria) in central Europe were also of special significance to ancient Rome, as they were very rich in high quality deposits of silver, as well as iron ore, some gold and rare earths. Giving Roma Nova extensive silver deposits provides a strong, plausible reason for its economic survival through the ages.

I also wanted my imaginary country to be near Italy and Austria for international connections. So it had to be in south central Europe. In the end, I pinched Carinthia in southern Austria, and northern Slovenia as my models. And in summer 2023, I went to the old Noricum capital of Virunum, near Klagenfurt in Austria and was thrilled to visit breathe in the air of ‘Roma Nova’.

Alison Morton © March, 2024

Alison’s social media links:

Connect with Alison on her thriller site: https://alison-morton.com

Facebook author page: https://www.facebook.com/AlisonMortonAuthor

X/Twitter: https://twitter.com/alison_morton @alison_morton

Alison’s writing blog: https://alisonmortonauthor.com

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/alisonmortonauthor/

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/5783095.Alison_Morton

Threads: https://www.threads.net/@alisonmortonauthor

Alison’s Amazon page: https://Author.to/AlisonMortonAmazon

Newsletter sign-up: https://www.alison-morton.com/newsletter/

Find all Helen’s books on her Amazon Author Page or order from any good bookstore:

Find all Helen’s books on her Amazon Author Page or order from any good bookstore: Before coming to Spain, I was living on the Ligurian coast of Italy – hence Ludo da Portovenere (the charismatic rogue of The Chosen Man Trilogy). The Genoese coastline creeps into Ludo’s narrative when, as an involuntary exile, he reminisces about his childhood.

Before coming to Spain, I was living on the Ligurian coast of Italy – hence Ludo da Portovenere (the charismatic rogue of The Chosen Man Trilogy). The Genoese coastline creeps into Ludo’s narrative when, as an involuntary exile, he reminisces about his childhood.

You can read about how my wicked hero Ludo da Portovenere creates mayhem in 17th Century Europe in three novels starting with The Chosen Man.

You can read about how my wicked hero Ludo da Portovenere creates mayhem in 17th Century Europe in three novels starting with The Chosen Man.  The Empress Emerald is available on:

The Empress Emerald is available on:

I had a rural childhood of the sort almost unimaginable today. I grew up over 50 years ago, roaming fields and woods and lanes on foot or on my bike, often alone. I watched the progression of wildflowers over the summer; I watched planting and harvest.

I had a rural childhood of the sort almost unimaginable today. I grew up over 50 years ago, roaming fields and woods and lanes on foot or on my bike, often alone. I watched the progression of wildflowers over the summer; I watched planting and harvest. The series isn’t set in the real world, but neither is it truly a fantasy world. There are no variations from the laws of physics or nature, only (barely) a fantasy geography. There are no fae or otherworldly creatures, only the flora and fauna of northern and central Europe.

The series isn’t set in the real world, but neither is it truly a fantasy world. There are no variations from the laws of physics or nature, only (barely) a fantasy geography. There are no fae or otherworldly creatures, only the flora and fauna of northern and central Europe. Many generations past, the great empire from the east left Lena’s country to its own defences. Now invasion threatens…and to save their land, women must learn the skills of war.

Many generations past, the great empire from the east left Lena’s country to its own defences. Now invasion threatens…and to save their land, women must learn the skills of war.

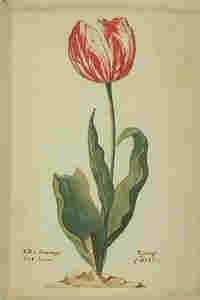

The first extract is from Book 1 of The Chosen Man Trilogy. It is 1635, charismatic Genoese merchant Ludovico da Portovenere (Ludo) is engaged in a conspiracy to inflate the tulip market in what became known as tulip fever. At this stage, readers are not sure whether Ludo is to be trusted, whether he’s a goodie or a baddie. How he handles his young Spanish servant Marcos here suggests he exploits people for his own ends. The dialogue also carries vital details about ‘tulipmania’.

The first extract is from Book 1 of The Chosen Man Trilogy. It is 1635, charismatic Genoese merchant Ludovico da Portovenere (Ludo) is engaged in a conspiracy to inflate the tulip market in what became known as tulip fever. At this stage, readers are not sure whether Ludo is to be trusted, whether he’s a goodie or a baddie. How he handles his young Spanish servant Marcos here suggests he exploits people for his own ends. The dialogue also carries vital details about ‘tulipmania’.

In Britain and Ireland, there was the added, critical risk of imminent invasion. It had happened in Poland and the Channel Islands, it could happen in Britain. The detail about the German U-boat surfacing off the Cornish coast to take on fresh water in Local Resistance was taken from a German sailor’s account. I didn’t invent that.

In Britain and Ireland, there was the added, critical risk of imminent invasion. It had happened in Poland and the Channel Islands, it could happen in Britain. The detail about the German U-boat surfacing off the Cornish coast to take on fresh water in Local Resistance was taken from a German sailor’s account. I didn’t invent that. How a Cornish fishing village uses its ancient smuggling tradition to evade rationing while preparing to defend their country when ‘Jerry’ landed forms the background to Local Resistance; how people as diverse as Land Army girls and cosmopolitan actors coped three years into the war underlies the shenanigans and criminal activities in Private Lives.

How a Cornish fishing village uses its ancient smuggling tradition to evade rationing while preparing to defend their country when ‘Jerry’ landed forms the background to Local Resistance; how people as diverse as Land Army girls and cosmopolitan actors coped three years into the war underlies the shenanigans and criminal activities in Private Lives.  by Mary Donnarumma Sharnick

by Mary Donnarumma Sharnick When I first visited Fiesole with my husband during the summer of 2002, I was smitten. With its ancient Etruscan walls, Roman baths and amphitheater, fourteenth-century town hall, the Monastery of San Francesco, several churches, the novice home of Fra Angelico in San Domenico, the town offered historical narratives at every turn. Villa Le Balze (Georgetown University’s study-abroad campus), Villa Sparta (former residence of the Greek royal family), and numerous other distinguished domiciles each offered detailed accounts about their inhabitants, visitors, interlopers, intimates, and detractors. Living in and near the town for periods of time over the course of the nineteenth- and twentieth-centuries have been: French writer Marcel Proust, American art historian Bernard Berenson, German painter Paul Klee, Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, and American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. The town is known as the most affluent suburb of Florence.

When I first visited Fiesole with my husband during the summer of 2002, I was smitten. With its ancient Etruscan walls, Roman baths and amphitheater, fourteenth-century town hall, the Monastery of San Francesco, several churches, the novice home of Fra Angelico in San Domenico, the town offered historical narratives at every turn. Villa Le Balze (Georgetown University’s study-abroad campus), Villa Sparta (former residence of the Greek royal family), and numerous other distinguished domiciles each offered detailed accounts about their inhabitants, visitors, interlopers, intimates, and detractors. Living in and near the town for periods of time over the course of the nineteenth- and twentieth-centuries have been: French writer Marcel Proust, American art historian Bernard Berenson, German painter Paul Klee, Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, and American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. The town is known as the most affluent suburb of Florence. Also illustrative of historical layering is the Hotel Villa Aurora, just steps from the bus stop in Piazza Mino. Recently closed, the hotel was still in 2018 housing visitors to Fiesole.

Also illustrative of historical layering is the Hotel Villa Aurora, just steps from the bus stop in Piazza Mino. Recently closed, the hotel was still in 2018 housing visitors to Fiesole. Every character must re-assess and re-consider what they knew or thought they knew in 1944, what they know or think they know in 1989. The inevitable and irrefutable corollary, of course, follows as a question: What is the relationship between the historical record and a human being’s experienced life? This is the question The Contessa’s Easel explores.

Every character must re-assess and re-consider what they knew or thought they knew in 1944, what they know or think they know in 1989. The inevitable and irrefutable corollary, of course, follows as a question: What is the relationship between the historical record and a human being’s experienced life? This is the question The Contessa’s Easel explores.

At midnight on a doom-laden Hallowe’en three young lasses sit round the hearth in the West Tower, gazing into the flames trying to divine their future. From this fortress perched high on a rocky outcrop on the banks of the River Tyne, accessible only by a narrow farm track, the powerful Hepburn family, the Earls of Bothwell, controlled the lands of East Lothian. Though now a ruin, this hidden gem retains many features still recognisable enough to fire the novelist’s imagination. In the Great Hall, the earls would host grand banquets prepared in the vaulted kitchen underneath where scullions would turn spits over huge fires; children would scamper up and down the turnpike staircases of the three towers, and prisoners would languish in the two pit prisons or oubliettes – one of which is said to have contained George Wishart after his arrest. What must it have been like to have been lowered down into a pit and left in complete darkness on a freezing winter’s night?

At midnight on a doom-laden Hallowe’en three young lasses sit round the hearth in the West Tower, gazing into the flames trying to divine their future. From this fortress perched high on a rocky outcrop on the banks of the River Tyne, accessible only by a narrow farm track, the powerful Hepburn family, the Earls of Bothwell, controlled the lands of East Lothian. Though now a ruin, this hidden gem retains many features still recognisable enough to fire the novelist’s imagination. In the Great Hall, the earls would host grand banquets prepared in the vaulted kitchen underneath where scullions would turn spits over huge fires; children would scamper up and down the turnpike staircases of the three towers, and prisoners would languish in the two pit prisons or oubliettes – one of which is said to have contained George Wishart after his arrest. What must it have been like to have been lowered down into a pit and left in complete darkness on a freezing winter’s night? Marie Macpherson hails from from the historic town of Musselburgh, six miles from the Scottish capital Edinburgh, but left the Honest Toun to study Russian at Strathclyde University. She spent a year in the former Soviet Union to research her PhD thesis on the 19th century Russian writer, Mikhail Lermontov, said to be descended from the poet and seer, Thomas the Rhymer.

Marie Macpherson hails from from the historic town of Musselburgh, six miles from the Scottish capital Edinburgh, but left the Honest Toun to study Russian at Strathclyde University. She spent a year in the former Soviet Union to research her PhD thesis on the 19th century Russian writer, Mikhail Lermontov, said to be descended from the poet and seer, Thomas the Rhymer.

The conspiracy theory behind Ludo’s actions is unproven, but the tulip bubble was very well documented at the time. Contemporary reports and records of sales transactions demonstrate the outrageous escalating prices paid up to 1637, when the bubble burst.

The conspiracy theory behind Ludo’s actions is unproven, but the tulip bubble was very well documented at the time. Contemporary reports and records of sales transactions demonstrate the outrageous escalating prices paid up to 1637, when the bubble burst. To write this second book I had to read about taxes and tariffs on cargoes from the East, about gems and silks, and secret treaties between England and Spain. Ludo becomes involved in delicate personal missions for two monarchs and sets in motion his vendetta on the Doria clan, who rejected his mother on her return to Liguria and exiled her to the castle in Porto Venere.

To write this second book I had to read about taxes and tariffs on cargoes from the East, about gems and silks, and secret treaties between England and Spain. Ludo becomes involved in delicate personal missions for two monarchs and sets in motion his vendetta on the Doria clan, who rejected his mother on her return to Liguria and exiled her to the castle in Porto Venere. Imagining these places in the past was not difficult, although Lisbon was effectively destroyed during a major earthquake in the 18th century, which made describing the old city rather more creative than factual.

Imagining these places in the past was not difficult, although Lisbon was effectively destroyed during a major earthquake in the 18th century, which made describing the old city rather more creative than factual. To write this part of the story I needed to find out what happened to certain gems, brooches, necklaces and pearl-studded hatbands belonging to the English Crown Jewels. Queen Henrietta Maria’s attempts to sell and pawn these royal heirlooms was well documented at the time, although a few, including the spinel clasp named The Three Brethren, did go astray. What Ludo does with the jewels is largely my invention, but a Portuguese Catholic princess did marry an English monarch so to an extent I was only playing with facts. It became a matter of ‘what if . . .’ combined with Ludo’s capacity for mischief.

To write this part of the story I needed to find out what happened to certain gems, brooches, necklaces and pearl-studded hatbands belonging to the English Crown Jewels. Queen Henrietta Maria’s attempts to sell and pawn these royal heirlooms was well documented at the time, although a few, including the spinel clasp named The Three Brethren, did go astray. What Ludo does with the jewels is largely my invention, but a Portuguese Catholic princess did marry an English monarch so to an extent I was only playing with facts. It became a matter of ‘what if . . .’ combined with Ludo’s capacity for mischief. This final story takes Ludo back Porto Venere. The name derives from a temple dedicated to the goddess Venus. I’d had the final scene of the trilogy in mind for a very long time, but writing it brought tears to my eyes. Ludo and Alina had become real people for me.

This final story takes Ludo back Porto Venere. The name derives from a temple dedicated to the goddess Venus. I’d had the final scene of the trilogy in mind for a very long time, but writing it brought tears to my eyes. Ludo and Alina had become real people for me. Each of the books in The Chosen Man Trilogy is a Readers’ Favorite 5*. If you have enjoyed the stories, please leave a review on your retailer’s site.

Each of the books in The Chosen Man Trilogy is a Readers’ Favorite 5*. If you have enjoyed the stories, please leave a review on your retailer’s site.