An Author in Exile

As many of my readers know, after travelling widely we finally settled down in southern Spain. Without knowing it beforehand, we moved into a locally renowned area for breeders of Pura Raza Español horses (known in UK and USA as Andalusians, I think). It was an ideal spot for me, but after the death of the last of our horses (at the ripe old age of 27), we decided the time had come to move nearer family and urban conveniences such as shops.

For my husband, this has been a return to his home province of Andalucía. For me, this (possibly) final-final move means accepting my voluntary exile as a ‘foreign wife’ is a permanent situation. My lifestyle has been more Latin than British for a long time now, but I still think of North Devon as home. Although to be honest I’m an exile in England these days as well: people do things differently there.

In my experience, being a voluntary exile is a combination of exciting new challenges, learning a language, buying new types of food etc, mixed with occasional bouts of irritation, annoyance and nostalgia. For a writer, however, it has certain advantages. Seeing one’s surroundings with an objective eye leads to a deeper awareness of both culture and the natural environment, which in Spain are closely connected. In the province of Madrid summers are very hot and winters are bitterly cold. As in many other provinces, there is barely a day of springtime or autumn as the year moves from one extreme to the other. So it is with many people: warm, close friendships, or the literally cold shoulder.

From the kitchen window of our new home, I can see the mauve-shaded Sierra de Málaga, where the Moors of Al-Ándalus harvested snow to keep medicines cool. On the other side of the house, beyond a set of hills, lies the now densely crowded Costa del Sol. A coastline once prey to the Barbary corsairs featured in The Chosen Man Trilogy and my current work-in-progress, The Doomsong Voyage. Away from tourist hot-spots, though, it is easy to drift into time travel: pretend there’s no road nearby or enter a small pueblo bar serving local wine or cider and it could be any century at all.

Before coming to Spain, I was living on the Ligurian coast of Italy – hence Ludo da Portovenere (the charismatic rogue of The Chosen Man Trilogy). The Genoese coastline creeps into Ludo’s narrative when, as an involuntary exile, he reminisces about his childhood.

Before coming to Spain, I was living on the Ligurian coast of Italy – hence Ludo da Portovenere (the charismatic rogue of The Chosen Man Trilogy). The Genoese coastline creeps into Ludo’s narrative when, as an involuntary exile, he reminisces about his childhood.

On occasions I had to curb Ludo’s nostalgia to prevent his story becoming a travel brochure: Portovenere, or Porto Venere, is very picturesque. Once the site of a Roman temple to Venus, it was the perfect location to conclude Ludo’s wicked adventures in By Force of Circumstance. I know this because I wasn’t just visiting: I was living there, buying groceries, taking children to school, being part of Italian daily life. Unconsciously, or sub-consciously I was stashing away sights, sounds and anecdotes for future historical crime novels. Authors in exile notice how people behave and interact. We tuck away special moments and the kernels of raw stories like squirrels in autumn. This is how my contribution to the new anthology Historical Stories of Exile came about.

Many years ago, a dear friend told me how her Polish parents met and married in post-war London. Her grandmother had walked from Warsaw to the Bosphorus with two daughters, found a passage to Spain, then to London. It took them two whole years to find a safety – in a city being bombed every night. I thought at the time it merited a full-length novel, but as I have never been to Poland and lack even a basic grasp of the language I didn’t feel up to the task. Nonetheless, the family’s experience stayed in my mind and eventually formed the background to my Victory in Exile short story (details below). The narrative itself links into my WWII Bob Robbins Home Front Mysteries series. It also includes elements told me by my Dutch neighbour when we were living in the Hague back in the ’90s. Ultimately, however, Victory in Exile reflects the current tragedy of innocent refugees trying to find a safe haven in a world at war.

I have never accepted the idea that a work of fiction can be reduced to its author’s life, but autobiographical moments do creep in, especially those related to the emotions. Here’s a scene from my first historical crime novel The Empress Emerald as an example. In the extract, a newly married, naïve Cornish girl arrives at her new family home in Jerez. It is 1920 in the story, what happens is a fictionalised version of my own arrival in Puerto Santa Maria in the 1980s.

The driver stopped the car outside two vast doors, blackened with age and reinforced with iron. They reminded Davina of an illustration in one of her big picture books: Bluebeard’s castle. As if by some sinister magic, a door swung open. Alfonso ushered her into a fern-infested patio. It smelt dank and uninviting. She looked up and around her. The patio was open to the sky, but on all four sides above there were windows. She sensed watching eyes and lowered her gaze.

The autobiographical element ends there. But my experience of being a voluntary exile obviously informs my writing. I know what it is like not to speak the language, not to share commonly acknowledged values; what it is like to be gaped at because your appearance or style doesn’t fit with the locals. I’ve been living in Spain, on and off, for years but people still ask me where I am from. I try not to bristle, and can’t help thinking about what being an involuntary exile must be like for those who can never go home.

J.G. Harlond

Find the new short story anthology Historical Stories of Exile at: https://mybook.to/StoriesOfExile

If you enjoy action-adventure travel stories and historical fiction here are a couple recommendations for a thumping good read:

- The Imp of Eye series by Kristin Gleeson: The Imp of Eye | Universal Book Links Help You Find Books at Your Favorite Store! (books2read.com)

- Helen Hollick’s Sea Witch series, which features a likeable rogue hero named Jesamiah Acorne: https://viewauthor.at/HelenHollick

You can read about how my wicked hero Ludo da Portovenere creates mayhem in 17th Century Europe in three novels starting with The Chosen Man.

You can read about how my wicked hero Ludo da Portovenere creates mayhem in 17th Century Europe in three novels starting with The Chosen Man.

Each story is based on some surprising and lesser-known real events involving the Vatican and crowned heads of Europe during the Thirty Years War and the English Civil War. http://getbook.at/TheChosenMan

The Empress Emerald is available on: https://mybook.to/p6ZMzs

The Empress Emerald is available on: https://mybook.to/p6ZMzs

While researching events in Britain during 1944, I came across a short comment made by someone on a history blog about how Churchill and Eisenhower met for an ultra-secret meeting at a private home on the east coast of Scotland in the month prior to D-Day.

While researching events in Britain during 1944, I came across a short comment made by someone on a history blog about how Churchill and Eisenhower met for an ultra-secret meeting at a private home on the east coast of Scotland in the month prior to D-Day.

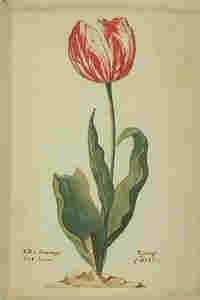

The first extract is from Book 1 of The Chosen Man Trilogy. It is 1635, charismatic Genoese merchant Ludovico da Portovenere (Ludo) is engaged in a conspiracy to inflate the tulip market in what became known as tulip fever. At this stage, readers are not sure whether Ludo is to be trusted, whether he’s a goodie or a baddie. How he handles his young Spanish servant Marcos here suggests he exploits people for his own ends. The dialogue also carries vital details about ‘tulipmania’.

The first extract is from Book 1 of The Chosen Man Trilogy. It is 1635, charismatic Genoese merchant Ludovico da Portovenere (Ludo) is engaged in a conspiracy to inflate the tulip market in what became known as tulip fever. At this stage, readers are not sure whether Ludo is to be trusted, whether he’s a goodie or a baddie. How he handles his young Spanish servant Marcos here suggests he exploits people for his own ends. The dialogue also carries vital details about ‘tulipmania’.