Secret Agents, Tulips, and the English Crown Jewels

The real history behind The Chosen Man Trilogy

Some authors are irritated by the question ‘where do you get your ideas from?’ but I see it as perfectly valid. Knowing the genesis of a good story can deepen its enjoyment or appreciation. In my case, however, it’s rather chicken and egg. Which came first, the idea for The Chosen Man and what became a trilogy, or the ideas generated out of the research? Historical fiction authors can probably relate to this; they may also agree that while research can take you down fascinating rabbit holes, some of the best bits have to be left out because readers almost certainly won’t believe it. This is what happened when I started gathering material about the first financial bubble known as tulipmania or tulip fever and Vatican secret agents for The Chosen Man. All of which was fascinating, but in many respects almost beggared belief.

But where did the idea come from? Well, the story began with a combination of events, one very real with devastating financial consequences, the other un-real, when I ‘saw’ people during a visit to Cotehele, a British National Trust property on the River Tamar in Cornwall and the model for the fictional house ‘Crimphele’ in my first novel. Wandering around the house mentally preparing the sequel to The Empress Emerald (set early 20th Century), I was beset by characters living in the 17th Century. To start with, the evil-minded McNab walked out of a wall, crossed the Great Hall and disappeared, then re-appeared later crossing the courtyard. He made my skin crawl, but he was not to be ignored. The portrait of a Stuart harridan gave me the unpleasant mother-in-law, and then to top it all, while I was gazing down at the Tamar Estuary from the roof of the Tudor tower I ‘saw’ Ludo da Portovenere arrive on a boat – much as he does at the end of the first book in the trilogy. So, I went home, set aside my original notes and started a new book entirely.

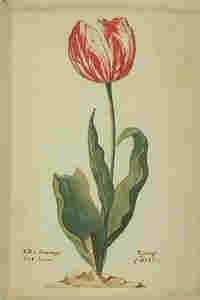

The story-line fell into place as I watched news coverage of the Lehman Brothers and mortgage scandals in the USA and I was reminded of the Dutch tulip bubble. During the 1630s in the Netherlands, or the United Provinces as the country was known then, tulip bulbs were worth more than their weight in gold. A virus which attacked the bulbs resulted in exotic stripes or ‘flames’ on petals, and a single rare bulb could cost three times the annual wage of a skilled artisan or even the price of an elegant house in Amsterdam. This was a period of intense political and religious intrigue in Europe. Spain was heavily involved in the Thirty Years War to regain Flanders; Pope Urban VIII was outwardly supporting Spain while conspiring to limit the size and power of the Holy Roman Empire, to which Habsburg Spain belonged; and France was playing both sides against the middle, harrying Spanish ships and playing double games with Rome. Having lived in the Netherlands I was well acquainted with the tulipmania, and it seemed quite plausible that a character such as Ludo might be employed as an agent provocateur in a conspiracy to undermine the burgeoning Protestant Dutch economy. Charismatic, wily Ludo is fictional, but he serves to show how just one man can create financial mayhem and ruin the lives of humble men and women in the process. Acting on behalf of the Spanish monarch and a Vatican cardinal, Ludo encourages and facilitates speculation on tulip bulbs.

The conspiracy theory behind Ludo’s actions is unproven, but the tulip bubble was very well documented at the time. Contemporary reports and records of sales transactions demonstrate the outrageous escalating prices paid up to 1637, when the bubble burst.

The conspiracy theory behind Ludo’s actions is unproven, but the tulip bubble was very well documented at the time. Contemporary reports and records of sales transactions demonstrate the outrageous escalating prices paid up to 1637, when the bubble burst.

The question is why did otherwise sober, thrifty Dutch men and women engage in what was basically gambling with flowers that for most of the year could not even be seen? The answer lies in a combination of factors overshadowed by the knowledge that Death was quite literally on their doorstep.

Amsterdam in 1635 was a thriving city driven by what we call the ‘work ethic’. Frippery and ostentation were frowned upon, so what could people who by their very thrift have acquired surplus income spend their money on? It had to be something that was not a visible luxury. Some people became patrons to up and coming artists, some became tulip connoisseurs. These exotic flowers, introduced into Holland from the land of the infidel, were defined as a ‘connoisseur item’ and were named after famous admirals and towns, and coveted. Within no time, otherwise sensible men and women began gambling on bulbs doubling or tripling their value in the space of a year, a month, a week – by 1636 prices were going up by the day. Men of both the professional and artisan classes, and many women, were spending their entire savings on bulbs, because money must not lie idle, and plague could kill an entire family in the space of one day.

One pamphlet of the time recorded the items and their value which were traded for a single Viceroy bulb. As you read, bear in mind the family of a shoemaker or baker lived on between 250 and 350 guilders* a year.

| Item | Value (florins*) |

| Two lasts of wheat | 448 |

| Four lasts of rye | 558 |

| Four fat oxen | 480 |

| Eight fat swine | 240 |

| Twelve fat sheep | 120 |

| Two hogsheads of wine | 70 |

| Four casks of beer | 32 |

| Two tons of butter | 192 |

| A complete bed | 100 |

| A suit of clothes | 80 |

| A silver drinking cup | 60 |

| Total | 2,500 |

(Guilders and florins* – the name of the currency used at this time varied from province to province. I opted to use guilders because it is the modern word for the currency.)

At its height, in the early spring of 1637, a Dutch merchant paid 6,650 guilders for a dozen tulip bulbs. Artisans pawned or sold their tools to ‘invest’ – largely thanks to Ludo da Portovenere, who brings bulbs from Constantinople then facilitates a futures market so humble men and women can participate in the fun. Ludo had access to the forbidden city because he was once a Barbary corsair and speaks the language.

As the trilogy progresses, Ludo gradually reveals his identity, or lack of it. His mother, a Doria, daughter of the Doge of Genoa, was captured by corsairs. Ludo was born in the Berber stronghold of Salé and raised by Murat Reïs, a renegade Dutchman named Jan Janszoon, who went into history as the infamous Murat Reïs the Younger, illustrious ancestor of the American Vanderbilt family, Jackie Onassis and Sir Winston Churchill.

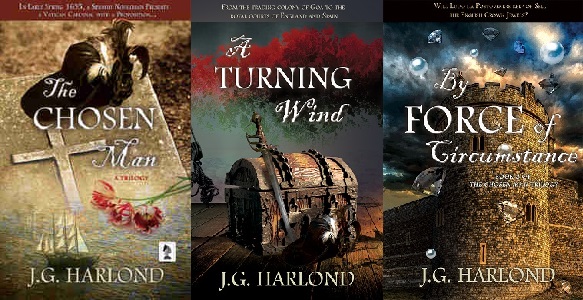

In Book 2, A Turning Wind, Ludo moves into the Portuguese Goan spice trade, but he is still pursued by the Vatican agent, Rogelio, who must destroy any evidence of the tulip conspiracy. Rogelio is part of the Vatican Black Order, sinister operatives and secret agents tasked with eliminating those who oppose or threaten the power of Rome. Here again, my background reading supplied much of the story – although this is where I also chose to leave out quite lot. The real history behind the Holy Alliance and the Black Order is hair-raising.

To write this second book I had to read about taxes and tariffs on cargoes from the East, about gems and silks, and secret treaties between England and Spain. Ludo becomes involved in delicate personal missions for two monarchs and sets in motion his vendetta on the Doria clan, who rejected his mother on her return to Liguria and exiled her to the castle in Porto Venere.

To write this second book I had to read about taxes and tariffs on cargoes from the East, about gems and silks, and secret treaties between England and Spain. Ludo becomes involved in delicate personal missions for two monarchs and sets in motion his vendetta on the Doria clan, who rejected his mother on her return to Liguria and exiled her to the castle in Porto Venere.

Agostino Doria was Doge of Genoa from 1600-1603. His family tree names each of his sons, but there is also an un-named daughter (who became Ludo’s mother). Having lived across the Gulf of La Spezia in Lerici, I knew a fair amount about Porto Venere. Each of the scenes there is written with the place very clearly in mind. Ludo, we learn is illegitimate, he is also ambitious and determined to get recompense for the way his mother was treated by her brothers, which is exactly what would have happened to any woman of ‘gentle birth’ who had been captured by corsairs: she could never hope to make a good marriage after that, her name was sullied.

As the story progresses, Ludo is sent to the Spanish court, which is passing the summer in El Escorial. He has been engaged by Charles Stuart to seek support from Catholic Spain for the coming Civil War in England. He is also charged by King Charles’ wife, the French Henrietta Maria, to help her sister Isabel, Queen of Spain. Both these commissions are based on real, albeit perhaps little-known affairs. During the early 1640s Spanish and English Ambassadors were drawing up a treaty that would enable Spanish troops to cross southern England as a land bridge to Flanders to avoid being attacked by the French. It was a tricky issue, the Protestant English celebrated the failure of Catholic Spain to invade Britain in 1588, the Spanish would not have been welcome, despite the fact that the West Country mainly favoured the Royalists during the subsequent war. Ludo becomes involved in these negotiations, and also in the Spanish queen’s private battle for control over her husband Felipe IV with his valido (First Minister and favourite) the infamous Conde-Duque de Olivares, and his Gorgon of a wife, Inez.

This became another moment where researching documented history uncovered details begging to be turned into fiction. The Conde-Duque was difficult, dangerous and spectacularly ugly. And in each respect, he and his wife were well-matched. Writing scenes involving these two real characters was as entertaining as it was challenging. A lot has been written (in Spanish) about both, so I had to choose my words carefully.

While researching Goa and the uncut-gem trade, I came across the writing of the French merchant-explorer Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (1605-1689) while preparing for A Turning Wind. In a spell-binding account of how diamonds were mined in the Golconda region of India, Tavernier quotes an account supposedly written by Marco Polo of how diamonds were found and traded in the area centuries before. It was too good not to use so I wove it into the opening scene. That, and the ancient ethical origins of the game Snakes and Ladders, created the background for Ludo’s second adventure, via documented history on Portugal and the ambitious Duchess of Braganza. This is where having lived in different countries and travelled pretty widely came in useful too. We had lived near El Escorial in the province of Madrid for a number of years, and I had visited Lisbon, Portugal, on various occasions.

Imagining these places in the past was not difficult, although Lisbon was effectively destroyed during a major earthquake in the 18th century, which made describing the old city rather more creative than factual.

Imagining these places in the past was not difficult, although Lisbon was effectively destroyed during a major earthquake in the 18th century, which made describing the old city rather more creative than factual.

Book 3, By Force of Circumstance, was helped along by a visit to a gin distillery in Plymouth (important research here!) and some astonishing facts relating to how Queen Henrietta Maria tried to raise money for Charles Stuart during the English Civil War. On a more serious level, one of the main themes in the trilogy shows how decisions made in high places can have appalling consequences for ordinary members of society. What happens to the main characters, Ludo, Alina and Marcos, is determined by a conflict not of their making, in a country not their own. Their efforts to safeguard their families was probably little different to what real people in their social circumstances experienced.

To write this part of the story I needed to find out what happened to certain gems, brooches, necklaces and pearl-studded hatbands belonging to the English Crown Jewels. Queen Henrietta Maria’s attempts to sell and pawn these royal heirlooms was well documented at the time, although a few, including the spinel clasp named The Three Brethren, did go astray. What Ludo does with the jewels is largely my invention, but a Portuguese Catholic princess did marry an English monarch so to an extent I was only playing with facts. It became a matter of ‘what if . . .’ combined with Ludo’s capacity for mischief.

To write this part of the story I needed to find out what happened to certain gems, brooches, necklaces and pearl-studded hatbands belonging to the English Crown Jewels. Queen Henrietta Maria’s attempts to sell and pawn these royal heirlooms was well documented at the time, although a few, including the spinel clasp named The Three Brethren, did go astray. What Ludo does with the jewels is largely my invention, but a Portuguese Catholic princess did marry an English monarch so to an extent I was only playing with facts. It became a matter of ‘what if . . .’ combined with Ludo’s capacity for mischief.

This final story takes Ludo back Porto Venere. The name derives from a temple dedicated to the goddess Venus. I’d had the final scene of the trilogy in mind for a very long time, but writing it brought tears to my eyes. Ludo and Alina had become real people for me.

This final story takes Ludo back Porto Venere. The name derives from a temple dedicated to the goddess Venus. I’d had the final scene of the trilogy in mind for a very long time, but writing it brought tears to my eyes. Ludo and Alina had become real people for me.

You can read more about the origins of the game Snakes and Ladders, Tavernier’s description of how men used eagles to acquire diamonds from pythons, and about the missing items belonging to the English Crown Jewels here in this blog.

Each of the books in The Chosen Man Trilogy is a Readers’ Favorite 5*. If you have enjoyed the stories, please leave a review on your retailer’s site.

Each of the books in The Chosen Man Trilogy is a Readers’ Favorite 5*. If you have enjoyed the stories, please leave a review on your retailer’s site.

The first Ludo story was inspired by a combination of two events; one very real with devastating financial consequences, the other un-real, other-worldly, when I ‘saw’ people during a visit to Cotehele in Cornwall (while preparing for another book altogether). Cotehele, a National Trust property on the River Tamar, became the fictional house Crimphele, then the story-line fell into place as I watched news coverage of the Lehman Brothers and mortgage scandals in the USA. I had lived in the Netherlands, was acquainted with the tulip bubble, and it seemed quite plausible that a character such as Ludo (the infamous ancestor of Leo Kazan in The Empress Emerald) might be employed as an agent provocateur acting for Habsburg Spain and, supposedly, for Rome. After fitting these elements together, I then had to learn some hard facts behind ‘tulip mania’ and some of the vaguer, barely credible history behind Vatican espionage and secret agents. It took a good two years to write The Chosen Man, fortunately reviews show it was all worthwhile.

The first Ludo story was inspired by a combination of two events; one very real with devastating financial consequences, the other un-real, other-worldly, when I ‘saw’ people during a visit to Cotehele in Cornwall (while preparing for another book altogether). Cotehele, a National Trust property on the River Tamar, became the fictional house Crimphele, then the story-line fell into place as I watched news coverage of the Lehman Brothers and mortgage scandals in the USA. I had lived in the Netherlands, was acquainted with the tulip bubble, and it seemed quite plausible that a character such as Ludo (the infamous ancestor of Leo Kazan in The Empress Emerald) might be employed as an agent provocateur acting for Habsburg Spain and, supposedly, for Rome. After fitting these elements together, I then had to learn some hard facts behind ‘tulip mania’ and some of the vaguer, barely credible history behind Vatican espionage and secret agents. It took a good two years to write The Chosen Man, fortunately reviews show it was all worthwhile. A long, long time ago I had a gap year job in a jewellery and antique shop, it wasn’t what I wanted to do for the rest of my life, but I learnt a lot and it helped greatly while preparing notes for A Turning Wind. During my research, I came across the writing of the French merchant-explorer Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (1605-1689). In a spell-binding account of how diamonds were mined in the Golconda region of India, Tavernier quotes an account supposedly written by Marco Polo of how diamonds were found and traded in the area centuries before. It was too good not to use so I wove it into the opening scene. That, and the ancient ethical origins of the game Snakes and Ladders, created the background for Ludo’s second adventure, via documented history on Portugal and the ambitious Duchess of Braganza, and a little known, unrealized treaty between Charles 1st and Felipe IV of Spain. Having spent many years living near El Escorial, the scenes set there with the infamous Conde-Duque de Olivares and Velazquez were easy to write.

A long, long time ago I had a gap year job in a jewellery and antique shop, it wasn’t what I wanted to do for the rest of my life, but I learnt a lot and it helped greatly while preparing notes for A Turning Wind. During my research, I came across the writing of the French merchant-explorer Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (1605-1689). In a spell-binding account of how diamonds were mined in the Golconda region of India, Tavernier quotes an account supposedly written by Marco Polo of how diamonds were found and traded in the area centuries before. It was too good not to use so I wove it into the opening scene. That, and the ancient ethical origins of the game Snakes and Ladders, created the background for Ludo’s second adventure, via documented history on Portugal and the ambitious Duchess of Braganza, and a little known, unrealized treaty between Charles 1st and Felipe IV of Spain. Having spent many years living near El Escorial, the scenes set there with the infamous Conde-Duque de Olivares and Velazquez were easy to write. One of my aims while writing this trilogy was to show how decisions made in high places can have appalling consequences for ordinary members of society. This story in particular shows how one’s personal destiny can be determined by events far beyond one’s control. The over-riding circumstance here is a civil war. What happens to Ludo, Alina and Marcos is determined by a conflict not of their making in a country not their own and their efforts to safeguard their families. Regrettably, it is something many readers can relate to nowadays.

One of my aims while writing this trilogy was to show how decisions made in high places can have appalling consequences for ordinary members of society. This story in particular shows how one’s personal destiny can be determined by events far beyond one’s control. The over-riding circumstance here is a civil war. What happens to Ludo, Alina and Marcos is determined by a conflict not of their making in a country not their own and their efforts to safeguard their families. Regrettably, it is something many readers can relate to nowadays.