Themes in fiction can be subtle or more evident, sometimes, I find, they creep in while the book is a work-in-progress. This happened with the ‘snakes and ladders’ motif in the third story in The Chosen Man Trilogy. I came across the origins of the game while researching the background to By Force of Circumstance and it fitted what was happening to the wily, unreliable Ludo da Portovenere so perfectly I knew I had to include it in the narrative.

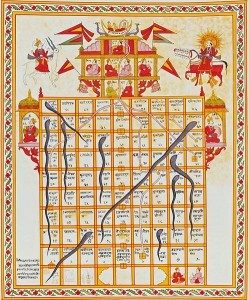

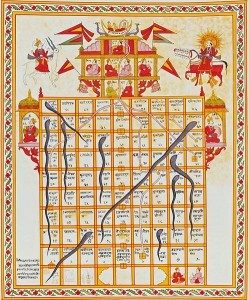

There are various theories and dates for how the game ‘snakes and ladders’ came about, but its origins are ancient and almost certainly ancient Asian. Originally called Mokshapat it was played with cowrie shells and dices. The ladders represented virtues, the snakes indicated vices, and the game demonstrated how good deeds take people to heaven and evil to the cycle of re-birth. An early version was devised or described by the 13th century poet Gyandev, but apart from its original intrinsic meaning, which has been lost, the game has undergone few modifications. The underlying meaning remained the same until it reached the west, where the more philosophical and didactic meaning was condensed to the chance and risk element of landing on a snake and slithering down to start all over again.

Snakes and ladders was played in India as one of many board and dice games, including pachisi (modern day Ludo), where it was known as moksha patam or vaikunthapaali or paramapada sopaanam, meaning the ‘ladder to salvation’ and emphasizing the role of fate or karma. A Jain version, Gyanbazi, has been dated back to the 16th century: a version called Leela reflects the Hindu concept of ‘consciousness’ in everyday life.

I came upon all this as I was reading and researching the historical background for my second story in The Chosen Man trilogy, which opens in 17th century Portuguese Goa. The original, ancient game fitted so perfectly with the story it became one of the main themes – the wily, unreliable Ludo is trying to make his fortune as a merchant, but he is also trying to find a meaning and focus for his life in general – so I knew I had to include it.

In the scene that follows, Ludo is on a trading voyage from Goa to Plymouth, his ship has anchored off an Omani beach and he has gone ashore to purchase pearls. Ludo sees two exquisite Arabian mares with their foals and finds his way to the local sheik intending to purchase them. Instead of the horse trading he’s expecting, however, he gets a lesson in destiny and desire.

*

1*

The sheik was seated on cushions in a high-ceilinged room. There were no intricate tiles such as those of the Arab homes Ludo knew in North Africa, only brightly coloured wall-hangings and mats, and on a low oblong table a large patchwork cloth.

The sheik was seated on cushions in a high-ceilinged room. There were no intricate tiles such as those of the Arab homes Ludo knew in North Africa, only brightly coloured wall-hangings and mats, and on a low oblong table a large patchwork cloth.

Ludo was led up to the sheik, who peered at him through unsmiling eyes then said, “You wish to take my joy from me and transport it across the world.”

“That is so, Excellency,” Ludo replied, wondering how he had divined where he wanted to take the mares having not thought it through himself.

The sheik stared at him until Ludo was forced to look away. Across the unfurnished room an eagle owl blinked, surprised perhaps to see a stranger. A small hawk chained to another perch shook its jesses. The owl had the same amber eyes as its master. Ludo shifted from one foot to the other, not unlike the smaller bird then, aware of what he had done and how it might be interpreted, stood straight, folding his arms across his chest.

The sheik, an elderly man similar in appearance to the pearl trader in a flowing white robe and square-set head cloth, tapped his beak-like nose. It was flattened at the tip. As Ludo’s vision became more accustomed to the low indoor light, he tried to decide if the flattening were natural or the result of an accident or fight, then chastised himself for becoming distracted and wondered how the sheik might be reading his features: the newly-grown beard that still itched, his Indian cotton pyjamas, his swollen, reddened hands from helping on deck after a long period of living in comfort.

Breaking the tension, the sheik snapped his fingers and a servant brought in a tray of sherbet and sugary date and almond morsels. He then indicated a cushion and invited Ludo to sit at the low table covered in a cloth with yellow and gold, white and red squares. Appliquéd onto the squares were fat, winding snakes and unstable ladders that tilted up and across the cloth. Words and phrases had been embroidered into certain squares in black but Ludo couldn’t read them.

“It was brought to my father’s father or perhaps his father’s father, many years ago from India,” the sheik said. “It is called moksha patam.” He placed two ebony white-spotted dice on the middle of the cloth.

“Ah, it is a game, like parchis.”

“Yes and no. Parchis requires a certain skill; moksha patam depends to a greater degree on the fall of the dice – and an individual’s luck.”

“A game of chance.”

“More than mere chance, my friend: truly it is a study in karma and kama; destiny and desire. We shall play together.”

“For the horses? If I win, I may take them?”

“No.”

“Then forgive my bad manners, Excellency, but I have no time for games.”

The sheik handed Ludo the dice. “As a guest you may throw first.”

Ludo delayed his response, taking a sip of sherbet to hide his annoyance; he was not in the mood for mystical games of chance, time wasted here could put his ship in jeopardy. If Tulip’s pursuers found their hiding place and he was not aboard . . . Ludo closed his eyes, not wanting to complete the thought, and rattled the dice in his accommodating palm out of sheer habit.

The sheik pointed to a ladder. “The ladders take you up to the end of the cloth and finally, if you win, bring you to ‘salvation’. The snakes take you down through your earthly vices. Look,” he pointed at the words stitched into the cloth, “your first chance to rise is through ‘faith’, then ‘reliability’, ‘generosity’, ‘knowledge’ and ‘asceticism’. But you can be brought back down again by ‘disobedience’, ‘vanity’, ‘vulgarity’, ‘drunkenness’ and ‘debt’. The longest and therefore the worst of these snakes are these which bring you back or near to the beginning, meaning you must start your climb all over again: watch out for ‘rage’ and ‘greed’, ‘pride’, ‘murder’ and ‘lust’. This one fat serpent here crossing the entire cloth is ‘lying’ – telling that which is not true.”

“There are fewer ladders than snakes,” Ludo said.

“Such is life.”

Ludo jiggled the dice. “And there is no one ladder that can take you straight to the top; but this snake up here can take me right back to the beginning.”

“No one single virtue is sufficient for salvation. What good is generosity if you are unreliable and guilty of greed and self-love?”

Trapped, Ludo tried to relax and indicated he was ready to begin. It was after all, only a game, although as the sheik had pointed out, not exactly a game for once he had begun he couldn’t help but wish for more virtues and lament his vices. In parchis, with a bit of cunning and friendly dice you could win within an hour. Not so here.

Ludo lost, devoured by the serpent of ‘disobedience’ twice, then ‘greed’ when he was close to finishing. He wanted to blame the sheik, who had maintained his scrutiny of his guest throughout, unnerving Ludo each time he threw.

Glad that it was over, Ludo tried to pull on his old mask of bonhomie and said cheerily, “Is there a prize for you, Excellency?”

“Is salvation not a prize?”

“I doubt I will ever find out, Excellency. Where I come from there’s no point even trying. And as I am no Hindustani I do not have to worry about the Wheel of Re-incarnation.” Across the room, the eagle owl glowered.

“Neither am I of Hind my friend, but I do believe a better life is attainable while we are on God’s earth. Only a complete fool dismisses the possibility of returning – being condemned on the Wheel.” The sheik drank from his cup of sherbet and ate a sweetmeat, taking his time.

Ludo forced himself not to squirm, pondering whether the actions related to ‘whim’ should be classified as a vice. Then his blood ran cold: on a whim he had walked into a trap. He had made himself a prisoner while the sheik’s men were unloading his ship. Rapidly he cast about for a guard but saw only the owl and the hawk; wisdom and aggression.

“You are nervous my friend. You fear I shall not let you go. You fear we shall take your cargo. It is within our power, but I would have hoped this past hour had shown you we are aware of the penalty of greed. Not that we have no need of your cargo. Spices from India, silks and tea from Cathay? You have tasted our sweetmeats: cinnamon from Ceylon would be most welcome here. Perhaps on your next voyage you will allow me to purchase from you?”

“Gladly, Excellency.” Ludo endeavoured to keep relief from his voice.

*

The game Ludo is playing here (and his name, shortened from Ludovico, is no accident) is far more complex than our children’s ‘Ludo’ or parchis, but the combination of skill and luck remain the same. The original game was a tool or means for teaching the effects of good deeds versus bad. As in this scene, the ladders represented virtues such as generosity, faith, and humility, while the snakes represented vices of lust, anger, murder, and theft. The moral to be learned was that a person can attain salvation (moksha) through doing good: doing evil one will lead to re-birth. The number of ladders was less than the number of snakes as a reminder that the path to salvation is full of obstacles and should be trod with caution. There were fewer ladders than snakes; as the sheik here says, such is life. In the game he and Ludo are playing, the squares of virtue are faith (12), reliability (51), generosity (57), knowledge (76), and asceticism (78). The squares of vice or evil are disobedience (41), vanity (44), vulgarity (49), theft (52), lying (58), drunkenness (62), debt (69), rage (84), greed (92), pride (95), murder (73), and lust (99); number 100 was salvation.

Ludo leaves the sheik a somewhat confused man without the mares he wished to buy. In the rest of the story we see him climb numerous ladders both physical and metaphorical, only to slip back down the fat snakes of ‘disobedience’, ‘greed’ and even ‘theft’ until chance, skill and luck redeem him and take him where he had not planned to be: a place offering the peace and contentment he didn’t know he was seeking.

*(1)The image above and some information on the of snakes and ladders comes from: http://iseeindia.com/2011/09/11/the-origin-of-snakes-and-ladders (accessed 23rd April, 2018 @ 11:21)

The Chosen Man and A Turning Wind are available from book stores and on-line retailers. The Amazon UK link for books by J.G. Harlond is: https://www.amazon.co.uk/s/ref=nb_sb_noss?url=search-alias%3Daps&field-keywords=+j.g.+harlond&rh=i%3Aaps%2Ck%3A+j.g.+harlond&ajr=0

This post was originally written for Antoine Vanner’s Dawlish Chronicles Blog: https://dawlishchronicles.com

In the year 1490, Brother Jacomo of Seville is sent to Brabant as a Papal Inquisitor. He loses no time in condemning a man to be burned alive in the main square of Den Bosch. It is a public warning: be sure your sins will find you out.

In the year 1490, Brother Jacomo of Seville is sent to Brabant as a Papal Inquisitor. He loses no time in condemning a man to be burned alive in the main square of Den Bosch. It is a public warning: be sure your sins will find you out.

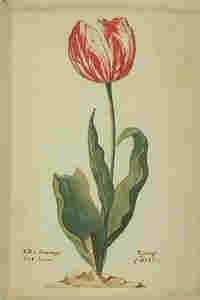

The conspiracy theory behind Ludo’s actions is unproven, but the tulip bubble was very well documented at the time. Contemporary reports and records of sales transactions demonstrate the outrageous escalating prices paid up to 1637, when the bubble burst.

The conspiracy theory behind Ludo’s actions is unproven, but the tulip bubble was very well documented at the time. Contemporary reports and records of sales transactions demonstrate the outrageous escalating prices paid up to 1637, when the bubble burst. To write this second book I had to read about taxes and tariffs on cargoes from the East, about gems and silks, and secret treaties between England and Spain. Ludo becomes involved in delicate personal missions for two monarchs and sets in motion his vendetta on the Doria clan, who rejected his mother on her return to Liguria and exiled her to the castle in Porto Venere.

To write this second book I had to read about taxes and tariffs on cargoes from the East, about gems and silks, and secret treaties between England and Spain. Ludo becomes involved in delicate personal missions for two monarchs and sets in motion his vendetta on the Doria clan, who rejected his mother on her return to Liguria and exiled her to the castle in Porto Venere. Imagining these places in the past was not difficult, although Lisbon was effectively destroyed during a major earthquake in the 18th century, which made describing the old city rather more creative than factual.

Imagining these places in the past was not difficult, although Lisbon was effectively destroyed during a major earthquake in the 18th century, which made describing the old city rather more creative than factual. To write this part of the story I needed to find out what happened to certain gems, brooches, necklaces and pearl-studded hatbands belonging to the English Crown Jewels. Queen Henrietta Maria’s attempts to sell and pawn these royal heirlooms was well documented at the time, although a few, including the spinel clasp named The Three Brethren, did go astray. What Ludo does with the jewels is largely my invention, but a Portuguese Catholic princess did marry an English monarch so to an extent I was only playing with facts. It became a matter of ‘what if . . .’ combined with Ludo’s capacity for mischief.

To write this part of the story I needed to find out what happened to certain gems, brooches, necklaces and pearl-studded hatbands belonging to the English Crown Jewels. Queen Henrietta Maria’s attempts to sell and pawn these royal heirlooms was well documented at the time, although a few, including the spinel clasp named The Three Brethren, did go astray. What Ludo does with the jewels is largely my invention, but a Portuguese Catholic princess did marry an English monarch so to an extent I was only playing with facts. It became a matter of ‘what if . . .’ combined with Ludo’s capacity for mischief. This final story takes Ludo back Porto Venere. The name derives from a temple dedicated to the goddess Venus. I’d had the final scene of the trilogy in mind for a very long time, but writing it brought tears to my eyes. Ludo and Alina had become real people for me.

This final story takes Ludo back Porto Venere. The name derives from a temple dedicated to the goddess Venus. I’d had the final scene of the trilogy in mind for a very long time, but writing it brought tears to my eyes. Ludo and Alina had become real people for me. Each of the books in The Chosen Man Trilogy is a Readers’ Favorite 5*. If you have enjoyed the stories, please leave a review on your retailer’s site.

Each of the books in The Chosen Man Trilogy is a Readers’ Favorite 5*. If you have enjoyed the stories, please leave a review on your retailer’s site.

The first Ludo story was inspired by a combination of two events; one very real with devastating financial consequences, the other un-real, other-worldly, when I ‘saw’ people during a visit to Cotehele in Cornwall (while preparing for another book altogether). Cotehele, a National Trust property on the River Tamar, became the fictional house Crimphele, then the story-line fell into place as I watched news coverage of the Lehman Brothers and mortgage scandals in the USA. I had lived in the Netherlands, was acquainted with the tulip bubble, and it seemed quite plausible that a character such as Ludo (the infamous ancestor of Leo Kazan in The Empress Emerald) might be employed as an agent provocateur acting for Habsburg Spain and, supposedly, for Rome. After fitting these elements together, I then had to learn some hard facts behind ‘tulip mania’ and some of the vaguer, barely credible history behind Vatican espionage and secret agents. It took a good two years to write The Chosen Man, fortunately reviews show it was all worthwhile.

The first Ludo story was inspired by a combination of two events; one very real with devastating financial consequences, the other un-real, other-worldly, when I ‘saw’ people during a visit to Cotehele in Cornwall (while preparing for another book altogether). Cotehele, a National Trust property on the River Tamar, became the fictional house Crimphele, then the story-line fell into place as I watched news coverage of the Lehman Brothers and mortgage scandals in the USA. I had lived in the Netherlands, was acquainted with the tulip bubble, and it seemed quite plausible that a character such as Ludo (the infamous ancestor of Leo Kazan in The Empress Emerald) might be employed as an agent provocateur acting for Habsburg Spain and, supposedly, for Rome. After fitting these elements together, I then had to learn some hard facts behind ‘tulip mania’ and some of the vaguer, barely credible history behind Vatican espionage and secret agents. It took a good two years to write The Chosen Man, fortunately reviews show it was all worthwhile. A long, long time ago I had a gap year job in a jewellery and antique shop, it wasn’t what I wanted to do for the rest of my life, but I learnt a lot and it helped greatly while preparing notes for A Turning Wind. During my research, I came across the writing of the French merchant-explorer Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (1605-1689). In a spell-binding account of how diamonds were mined in the Golconda region of India, Tavernier quotes an account supposedly written by Marco Polo of how diamonds were found and traded in the area centuries before. It was too good not to use so I wove it into the opening scene. That, and the ancient ethical origins of the game Snakes and Ladders, created the background for Ludo’s second adventure, via documented history on Portugal and the ambitious Duchess of Braganza, and a little known, unrealized treaty between Charles 1st and Felipe IV of Spain. Having spent many years living near El Escorial, the scenes set there with the infamous Conde-Duque de Olivares and Velazquez were easy to write.

A long, long time ago I had a gap year job in a jewellery and antique shop, it wasn’t what I wanted to do for the rest of my life, but I learnt a lot and it helped greatly while preparing notes for A Turning Wind. During my research, I came across the writing of the French merchant-explorer Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (1605-1689). In a spell-binding account of how diamonds were mined in the Golconda region of India, Tavernier quotes an account supposedly written by Marco Polo of how diamonds were found and traded in the area centuries before. It was too good not to use so I wove it into the opening scene. That, and the ancient ethical origins of the game Snakes and Ladders, created the background for Ludo’s second adventure, via documented history on Portugal and the ambitious Duchess of Braganza, and a little known, unrealized treaty between Charles 1st and Felipe IV of Spain. Having spent many years living near El Escorial, the scenes set there with the infamous Conde-Duque de Olivares and Velazquez were easy to write. One of my aims while writing this trilogy was to show how decisions made in high places can have appalling consequences for ordinary members of society. This story in particular shows how one’s personal destiny can be determined by events far beyond one’s control. The over-riding circumstance here is a civil war. What happens to Ludo, Alina and Marcos is determined by a conflict not of their making in a country not their own and their efforts to safeguard their families. Regrettably, it is something many readers can relate to nowadays.

One of my aims while writing this trilogy was to show how decisions made in high places can have appalling consequences for ordinary members of society. This story in particular shows how one’s personal destiny can be determined by events far beyond one’s control. The over-riding circumstance here is a civil war. What happens to Ludo, Alina and Marcos is determined by a conflict not of their making in a country not their own and their efforts to safeguard their families. Regrettably, it is something many readers can relate to nowadays.

I self-published the first title, Warhorn – Sons of Iberia, in 2013 and the fourth will be available in the Spring of 2019. The series is set during the 2nd Punic War which was fought between Carthage and Rome between 218BC and 202BC.

I self-published the first title, Warhorn – Sons of Iberia, in 2013 and the fourth will be available in the Spring of 2019. The series is set during the 2nd Punic War which was fought between Carthage and Rome between 218BC and 202BC. While the ancient people of Iberia are long gone, their land remains largely unchanged and just as dramatic. The river Tagus which flows a thousand kilometers across Spain and Portugal to the Atlantic from its wellspring in the Fuente de García. The wild coast of the Costa Brava. The moon-like Bardenas Reales. Interesting local settings are vital in creating depth and atmosphere in any tale and from the beautiful blue coastal waters of the Mediterranean to the high mountains of the Pyrenees, Iberia offers a palette of landscapes in which countless deeds of heroism wait to unfold.

While the ancient people of Iberia are long gone, their land remains largely unchanged and just as dramatic. The river Tagus which flows a thousand kilometers across Spain and Portugal to the Atlantic from its wellspring in the Fuente de García. The wild coast of the Costa Brava. The moon-like Bardenas Reales. Interesting local settings are vital in creating depth and atmosphere in any tale and from the beautiful blue coastal waters of the Mediterranean to the high mountains of the Pyrenees, Iberia offers a palette of landscapes in which countless deeds of heroism wait to unfold. Other wonderful creatures that still roam the wilds of Iberia include the endangered Iberian lynx, brown bear, and Spanish Ibex. The Iberian lynx often features in Sons of Iberia and I begin the series through the eyes of a lynx.

Other wonderful creatures that still roam the wilds of Iberia include the endangered Iberian lynx, brown bear, and Spanish Ibex. The Iberian lynx often features in Sons of Iberia and I begin the series through the eyes of a lynx. Glenn Bauer – Sources and links:

Glenn Bauer – Sources and links: It is 80 years now since Daphne du Maurier’s novel Rebecca was first released. Back in 1938, du Maurier’s publishers were nervous about the novel’s future, but the story has become a classic: a world-wide favourite, a play, a television series, even an iconic black and white movie. For a while, back in the 90s, new editions of du Maurier’s novels were hard to obtain, but with the recent film version of My Cousin Rachel she is very much back in the public eye.

It is 80 years now since Daphne du Maurier’s novel Rebecca was first released. Back in 1938, du Maurier’s publishers were nervous about the novel’s future, but the story has become a classic: a world-wide favourite, a play, a television series, even an iconic black and white movie. For a while, back in the 90s, new editions of du Maurier’s novels were hard to obtain, but with the recent film version of My Cousin Rachel she is very much back in the public eye. Big houses, full of private tragedies and secret histories, feature in many of her novels. Looking at photographs of Menabilly I wonder if that house stands as a metaphor for her fiction – as full of conflicting emotions, versions of the past and fantasies as the house on the strand. Such thoughts and ideas are only suggested, it is up to each reader to interpret them of course, and as in real life we interpret them according to our own way of thinking and personal experiences. Readers bring their own baggage to any book.

Big houses, full of private tragedies and secret histories, feature in many of her novels. Looking at photographs of Menabilly I wonder if that house stands as a metaphor for her fiction – as full of conflicting emotions, versions of the past and fantasies as the house on the strand. Such thoughts and ideas are only suggested, it is up to each reader to interpret them of course, and as in real life we interpret them according to our own way of thinking and personal experiences. Readers bring their own baggage to any book. This post first appeared in the Discovering Diamonds blog:

This post first appeared in the Discovering Diamonds blog:  Healthy, well-trained horses entered in modern long-distance races, sometimes called endurance races (for a very good reason) can cover up to 100 miles in a day. The favoured breed is the Arabian, but while the type of breed matters, it’s the training that is important. Each mount has to be prepared for these distances over a long period of time, and this includes getting used to eating hard fodder at different times of the day, which many horses do not or will not do.

Healthy, well-trained horses entered in modern long-distance races, sometimes called endurance races (for a very good reason) can cover up to 100 miles in a day. The favoured breed is the Arabian, but while the type of breed matters, it’s the training that is important. Each mount has to be prepared for these distances over a long period of time, and this includes getting used to eating hard fodder at different times of the day, which many horses do not or will not do. A final word: these blog posts are written from my personal experience of a life-time caring for and training horses. If you go to other on-line sources you may find conflicting or differing information.

A final word: these blog posts are written from my personal experience of a life-time caring for and training horses. If you go to other on-line sources you may find conflicting or differing information. The sheik was seated on cushions in a high-ceilinged room. There were no intricate tiles such as those of the Arab homes Ludo knew in North Africa, only brightly coloured wall-hangings and mats, and on a low oblong table a large patchwork cloth.

The sheik was seated on cushions in a high-ceilinged room. There were no intricate tiles such as those of the Arab homes Ludo knew in North Africa, only brightly coloured wall-hangings and mats, and on a low oblong table a large patchwork cloth.

It was the summer of 2001. I picked up a leaflet about an exhibition that was to be held in the museum at Madinat al-Zahra. It was entitled The Splendour of the

It was the summer of 2001. I picked up a leaflet about an exhibition that was to be held in the museum at Madinat al-Zahra. It was entitled The Splendour of the  Once the seat of power had been removed from Madinat al-Zahra, the city went into decline. The wealthy citizens left, quickly followed by the artisans, builders, merchants and local businessmen. Its beautiful buildings were looted and stripped of their treasures and the buildings were destroyed to provide materials for other uses. Today you can find artefacts from the city in Málaga, Granada, and elsewhere.

Once the seat of power had been removed from Madinat al-Zahra, the city went into decline. The wealthy citizens left, quickly followed by the artisans, builders, merchants and local businessmen. Its beautiful buildings were looted and stripped of their treasures and the buildings were destroyed to provide materials for other uses. Today you can find artefacts from the city in Málaga, Granada, and elsewhere.