Blending Facts Into Fiction

by Helen Hollick

My Sea Witch Voyages are nautical adventure yarns set in the Golden Age of piracy, the early 1700s. As with many a typical sailor’s yarn, part of the tales are solid sailing facts, others can be distinctly fanciful. That blend of fiction – even fantasy – is made believable by the inclusion of facts. Get the facts right, then a reader will believe the fictional bits.

I use several real historical figures as additional characters alongside my scallywag protagonist, Captain Jesamiah Acorne, because the history is important as a background to his various sea-going adventures.

I use several real historical figures as additional characters alongside my scallywag protagonist, Captain Jesamiah Acorne, because the history is important as a background to his various sea-going adventures.

In the latest Voyage, Gallows Wake, Jesamiah meets up with Edward Vernon, who was a real, respected Admiral. But in my story, set in 1719, Vernon is still a relatively unknown Captain. Jesamiah has had a run-in with him in the past (in the second Voyage, Pirate Code) and here they are, to meet again.

I’ve invented this part of Vernon’s career, of course, but in factual history, Vernon had a long and highly distinguished career, after forty-six years of service, becoming an admiral. Born in November 1684, he died in October 1757, making him thirty-five at the time when Gallows Wake is set.

In 1739 Vernon was responsible for the capture of Porto Bello, during the War of Jenkins’ Ear. He served as a Member of Parliament on three occasions, and had a reputation of being particularly outspoken on naval matters, making him a somewhat controversial figure.

I expect you have heard the slang term ‘Grog’ for rum which has been diluted with water? ‘Grog’ is attributed to Vernon, whose nickname was ‘Old Grog’. He was well known for wearing coats made of grogram material. Originally, this was Grosgrain a corruption of the French word. Gros gram is a coarse, loosely woven fabric of silk, silk and mohair, or silk and wool. Gros means thick or coarse, while grain is from Old French graine from either seed or texture. Vernon introduced watered rum into his naval squadron, which the sailors soon began to call ‘Grog’.

Vernon is also the eponym of George Washington’s estate Mount Vernon, and the many places in the United States which are named after it. George Washington’s older half-brother served on Vernon’s flagship HMS Princess Caroline in 1741. In honour of his former commander, he named his Virginia estate Mount Vernon.

I have slightly altered some of the dates and places in order to put Vernon where I wanted him in the summer and autumn of 1719 – Gibraltar and Spain, (he was possibly in the Baltic, in fact) so the events that happen in Gallows Wake are entirely fictitious, but the man himself is not.

It was quite fun giving him an adventure with my Jesamiah Acorne.

Read an excerpt from Gallows Wake

“Captain?”

Edward Vernon looked up from the letter he was writing, annoyed at being disturbed in the sanctity of his Great Cabin, but half expecting it. They were not long under way and there was always uncertainty during the first hours of making sail. Especially where his dithering second lieutenant was concerned. A young man of nineteen years old, he had the prospect of a good future ahead of him were he only to apply himself, but Lieutenant Lancelot Lande well-earned his nickname of ‘Three Ells’, for his name, his general uncertainty and over-used, ‘Look Lively Lads’ the latter two of which the bosun, Almitty, seized upon to make use of his cane. Not that Vernon disapproved of genuine discipline – far from it – but unnecessary brutality soured the men, and there was a loyal, hard-working crew aboard Bonne Chance. Despite the sadistic nature of ‘Gawd Almighty’, Mr Almitty.

Lande entered, did not stoop low enough beneath the overhead beams and knocked his hat off. He blushed, retrieved it and stood smartly before Vernon’s desk, which even after this short time at sea was already littered with cluttered paraphernalia.

“My apologies for interrupting your solitude, Captain. Writing to your lady wife, are you? I will do so to my dear mama, if ever I find the time. Not that she appreciates letters pertaining to a nautical bent, but…”

“Yes, Mr Lande, I pen a paragraph or two for Mrs Vernon at the close of every day. How may I help you?”

Mr Lande twirled his hat between his stubby fingers. “Well, ’tis a tad unorthodox, but there’s a chap aboard, a passenger bound for Cádiz. He is something to do with the children we have aboard.”

Vernon focused on the hat. How many times had he told Lande not to wear the thing below deck – for the reason shown. Low ceiling beams and the height of men were incompatible. Hats got knocked off, and looked comical in the eyes of the crew and undignified for the officers. Ignoring the hat issue, he said, “The children, and their escort, are of no consequence to me Mr Lande. I have made it quite clear that they are to remain below and out of our way. Fortunately, it is but a short voyage to our destination. I estimate, twelve, sixteen hours at most if wind and weather suit?”

“Aye, indeed, sir.”

“So, what is the problem? Everything is in order, is it not? Where is Mr Coffney?” Vernon faked a smile, despite his irritation.

“First Lieutenant Coffney is busy, sir, with an incident concerning one of the men.”

An incident? Something I should be informed of? Vernon wondered, then dismissed the thought. Unlike Lande, Coffney was a capable officer, and obviously the matter was of no large consequence, else he would have been informed of it.

“I am more than content to leave our passage and those children in the capable hands of yourself and Lieutenant Coffney.” Vernon indicated his letter. “So, I would very much like to finish this paragraph and then seek my cot. It is, after all,” he extracted a pocket watch from his waistcoat, flipped its gold protective case open and studied the hour. “It is approaching a quarter less eleven of the clock. Should these children not be snuggled in their blankets, and asleep?”

Lande did not return the smile. “I think they are, sir. I apologise for the interruption, but it is not about the children. Least, I do not think it is. Mayhap it will wait until morning? Although he was most insistent.”

“He?”

“Our passenger.”

“Is it, then, important?”

“The gentleman said it was.”

Give me strength, Vernon thought; said with patience, “Who is this gentleman? What does he want?”

“What he wants I do not know, sir, but he said he requires to speak in private with you as a matter of urgency. He made the request to Lieutenant Coffney as soon as he came aboard, before we sailed.”

“And you have only now brought the matter to my attention?”

“Aye, sir. We were busy getting under way and Mr Coffney did not wish to disturb you.”

“But you feel I may be disturbed now?”

“The gentleman has been most persistent. He says it is government business.”

Vernon pursed his lips. So, this was the government representative for these blasted children? As a captain, Vernon considered that he was perfectly capable of delivering them to their devoted parents without some fop of a government attaché interfering. He sighed. Could there be more to this mission than he perceived?

“I had better see him. Please show him in, Mr Lande.”

Lande gestured a salute, made to replace his hat, thought better of it and tucked the thing beneath his arm. “Very good, sir.”

Vernon returned to his letter, heard someone enter, did not look up but continued writing.

A soft cough.

He finished the sentence, placed the quill pen in the inkpot, dusted the letter with sand, then sat back in his chair, folding his hands over his stomach. Looked at a cleanshaven, well-dressed man of about his own height of four inches under the six foot, but a little stouter of build. Hat tucked beneath his arm, he made a slight, respectful bow. Vernon noticed that his hands were work-worn and bore a slight trace of tar beneath the nails. No rough sailor, but a man who knew work when required?

“Good evening to you, sir,” Vernon said, congenially, but with a little curiosity to his tone. “How may I be of assistance?”

THE VOYAGES:

SEA WITCH Voyage one

PIRATE CODE Voyage two

BRING IT CLOSE Voyage three

RIPPLES IN THE SAND Voyage four

ON THE ACCOUNT Voyage five

WHEN THE MERMAID SINGS – a prequel to the series (short-read novella)

And just published… GALLOWS WAKE

The Sixth Voyage of Captain Jesamiah Acorne

by Helen Hollick

Where the Past haunts the future…

Damage to her mast means Sea Witch has to be repaired, but the nearest shipyard is at Gibraltar. Unfortunately for Captain Jesamiah Acorne, several men he does not want to meet are also there, among them, Captain Edward Vernon of the Royal Navy, who would rather see Jesamiah hang.

Then there is the spy, Richie Tearle, and manipulative Ascham Doone who has dubious plans of his own. Plans that involve Jesamiah, who, beyond unravelling the puzzle of a dead person who may not be dead, has a priority concern regarding the wellbeing of his pregnant wife, the white witch, Tiola.

Forced to sail to England without Jesamiah, Tiola must keep herself and others close to her safe, but memories of the past, and the shadow of the gallows haunt her. Dreams disturb her, like a discordant lament at a wake.

But is this the past calling, or the future?

From the first review of Gallows Wake:

“Hollick’s writing is crisp and clear, and her ear for dialogue and ability to reveal character in a few brief sentences is enviable. While several of the characters in Gallows Wake have returned from previous books, I felt no need to have read those books to understand them. The paranormal side of the story—Tiola is a white witch, with powers of precognition and more, and one of the characters is not quite human—blends with the story beautifully, handled so matter-of-factly. This is simply Jesamiah’s reality, and he accepts it, as does the reader.”

Author Marian L. Thorpe.

BUY LINKS:

Amazon Author Page (Universal link): https://viewauthor.at/HelenHollick

Where you will find the entire series waiting at anchor in your nearest Amazon harbour – do come aboard and share Jesamiah’s derring-do nautical adventures! Available Kindle, Kindle Unlimited and in paperback. Or order a copy from your local bookstore!

ABOUT HELEN HOLLICK

ABOUT HELEN HOLLICK

First accepted for traditional publication in 1993, Helen became a USA Today Bestseller with her historical novel, The Forever Queen (titled A Hollow Crown in the UK) with the sequel, Harold the King (US: I Am The Chosen King) being novels that explore the events that led to the Battle of Hastings in 1066. Her Pendragon’s Banner Trilogy is a fifth-century version of the Arthurian legend, and she writes a nautical adventure/fantasy series, The Sea Witch Voyages.

Helen is now also branching out into the quick read novella, ‘Cosy Mystery’ genre with her Jan Christopher Murder Mysteries, set in the 1970s, with the first in the series, A Mirror Murder incorporating her often hilarious memories of working as a library assistant.

Her non-fiction books are Pirates: Truth and Tales and Life of A Smuggler. She lives with her family in an eighteenth-century farmhouse in North Devon and occasionally gets time to write…

Website: www.helenhollick.net

Newsletter Subscription: http://tinyletter.com/HelenHollick

Blog: www.ofhistoryandkings.blogspot.com

Facebook: www.facebook.com/HelenHollick

Twitter: @HelenHollick https://twitter.com/HelenHollick

From my desk here in the Province of Málaga I can see the Sierra de Las Nieves. This was where the Moors of Al-Ándalus used to harvest snow to be collected in summer for sherbet and to keep medicines cool. To the right out of a large picture window is the bandalero country of The Empress Emerald; to the left, beyond mauve-shaded mountains, are ancient fishing villages now known as the Costa del Sol, but once prey to the Barbary corsairs featured in The Chosen Man Trilogy.

From my desk here in the Province of Málaga I can see the Sierra de Las Nieves. This was where the Moors of Al-Ándalus used to harvest snow to be collected in summer for sherbet and to keep medicines cool. To the right out of a large picture window is the bandalero country of The Empress Emerald; to the left, beyond mauve-shaded mountains, are ancient fishing villages now known as the Costa del Sol, but once prey to the Barbary corsairs featured in The Chosen Man Trilogy.

Despite my somewhat Latinized outlook, though, what I see through my Spanish picture window when I am at my desk in Málaga is still with a realistic Englishwoman’s eyes.

Despite my somewhat Latinized outlook, though, what I see through my Spanish picture window when I am at my desk in Málaga is still with a realistic Englishwoman’s eyes. If, like me, you enjoy novels that takes you into the past and/or far away, check out the excellent Bristish historical fiction author, Deborah Swift. She has a new novel set in 17th century Italy out now, too.

If, like me, you enjoy novels that takes you into the past and/or far away, check out the excellent Bristish historical fiction author, Deborah Swift. She has a new novel set in 17th century Italy out now, too. If you enjoy gritty, contemporary British police crime fiction, try B.A. Morton’s frightening, heart-rending ‘Crime on the Tyne’.

If you enjoy gritty, contemporary British police crime fiction, try B.A. Morton’s frightening, heart-rending ‘Crime on the Tyne’.

The first extract is from Book 1 of The Chosen Man Trilogy. It is 1635, charismatic Genoese merchant Ludovico da Portovenere (Ludo) is engaged in a conspiracy to inflate the tulip market in what became known as tulip fever. At this stage, readers are not sure whether Ludo is to be trusted, whether he’s a goodie or a baddie. How he handles his young Spanish servant Marcos here suggests he exploits people for his own ends. The dialogue also carries vital details about ‘tulipmania’.

The first extract is from Book 1 of The Chosen Man Trilogy. It is 1635, charismatic Genoese merchant Ludovico da Portovenere (Ludo) is engaged in a conspiracy to inflate the tulip market in what became known as tulip fever. At this stage, readers are not sure whether Ludo is to be trusted, whether he’s a goodie or a baddie. How he handles his young Spanish servant Marcos here suggests he exploits people for his own ends. The dialogue also carries vital details about ‘tulipmania’.

In Britain and Ireland, there was the added, critical risk of imminent invasion. It had happened in Poland and the Channel Islands, it could happen in Britain. The detail about the German U-boat surfacing off the Cornish coast to take on fresh water in Local Resistance was taken from a German sailor’s account. I didn’t invent that.

In Britain and Ireland, there was the added, critical risk of imminent invasion. It had happened in Poland and the Channel Islands, it could happen in Britain. The detail about the German U-boat surfacing off the Cornish coast to take on fresh water in Local Resistance was taken from a German sailor’s account. I didn’t invent that. How a Cornish fishing village uses its ancient smuggling tradition to evade rationing while preparing to defend their country when ‘Jerry’ landed forms the background to Local Resistance; how people as diverse as Land Army girls and cosmopolitan actors coped three years into the war underlies the shenanigans and criminal activities in Private Lives.

How a Cornish fishing village uses its ancient smuggling tradition to evade rationing while preparing to defend their country when ‘Jerry’ landed forms the background to Local Resistance; how people as diverse as Land Army girls and cosmopolitan actors coped three years into the war underlies the shenanigans and criminal activities in Private Lives.

The Laundry Room is an example. It all began with a promise and a prayer. The new rabbi at my synagogue stood on the pulpit of his congregation during the High Holidays promising to take a group to Israel in the near future. My husband and I were two of the first to sign up.

The Laundry Room is an example. It all began with a promise and a prayer. The new rabbi at my synagogue stood on the pulpit of his congregation during the High Holidays promising to take a group to Israel in the near future. My husband and I were two of the first to sign up. The traffic was almost as bad as New York’s. Our first stop was on the Mount of Olives, a part of the Judaean Mountain chain and the ancient Judean kingdom. It was there we beheld Jerusalem and all of its splendor as the sun set in the west, casting a golden glow over the city, hence Jerusalem of Gold, a popular Israeli song. We left the mountain and headed toward the coast and the center of Tel Aviv, a thriving metropolis with signs of bombed buildings next to new. The contrast was startling to say the least.

The traffic was almost as bad as New York’s. Our first stop was on the Mount of Olives, a part of the Judaean Mountain chain and the ancient Judean kingdom. It was there we beheld Jerusalem and all of its splendor as the sun set in the west, casting a golden glow over the city, hence Jerusalem of Gold, a popular Israeli song. We left the mountain and headed toward the coast and the center of Tel Aviv, a thriving metropolis with signs of bombed buildings next to new. The contrast was startling to say the least. Little remains, but some of the mosaics that have managed to survive time and ware, are magnificent. The clear, aqua waters of the Mediterranean wash gently upon the shore, spilling over into the largest natural pool I’ve ever seen.

Little remains, but some of the mosaics that have managed to survive time and ware, are magnificent. The clear, aqua waters of the Mediterranean wash gently upon the shore, spilling over into the largest natural pool I’ve ever seen. I could go on and on, but for some reason, it was the Ayalon Institute that held fast. I tried to do some research when I returned home, but there was little. I wrote to the institute to ask for a brochure, but instead received a personal email from a Judith Ayalon, one of the 45 youth that built, supplied, and ran an underground ammunition factory that would play a major role in the establishment of Israel as an independent country. She and I would correspond for the next two years. The visual of teenagers fashioning bullet casings out of copper or filling those casings with gunpowder is hard to erase. There was nothing special or memorable about the terrain, but what took place there will never be erased from my mind. A well-kept secret until 1986, this historic site has become a major stop for those visiting Israel and a place I will never forget. The Laundry Room covers those historic events from beginning to end.

I could go on and on, but for some reason, it was the Ayalon Institute that held fast. I tried to do some research when I returned home, but there was little. I wrote to the institute to ask for a brochure, but instead received a personal email from a Judith Ayalon, one of the 45 youth that built, supplied, and ran an underground ammunition factory that would play a major role in the establishment of Israel as an independent country. She and I would correspond for the next two years. The visual of teenagers fashioning bullet casings out of copper or filling those casings with gunpowder is hard to erase. There was nothing special or memorable about the terrain, but what took place there will never be erased from my mind. A well-kept secret until 1986, this historic site has become a major stop for those visiting Israel and a place I will never forget. The Laundry Room covers those historic events from beginning to end. by Mary Donnarumma Sharnick

by Mary Donnarumma Sharnick When I first visited Fiesole with my husband during the summer of 2002, I was smitten. With its ancient Etruscan walls, Roman baths and amphitheater, fourteenth-century town hall, the Monastery of San Francesco, several churches, the novice home of Fra Angelico in San Domenico, the town offered historical narratives at every turn. Villa Le Balze (Georgetown University’s study-abroad campus), Villa Sparta (former residence of the Greek royal family), and numerous other distinguished domiciles each offered detailed accounts about their inhabitants, visitors, interlopers, intimates, and detractors. Living in and near the town for periods of time over the course of the nineteenth- and twentieth-centuries have been: French writer Marcel Proust, American art historian Bernard Berenson, German painter Paul Klee, Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, and American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. The town is known as the most affluent suburb of Florence.

When I first visited Fiesole with my husband during the summer of 2002, I was smitten. With its ancient Etruscan walls, Roman baths and amphitheater, fourteenth-century town hall, the Monastery of San Francesco, several churches, the novice home of Fra Angelico in San Domenico, the town offered historical narratives at every turn. Villa Le Balze (Georgetown University’s study-abroad campus), Villa Sparta (former residence of the Greek royal family), and numerous other distinguished domiciles each offered detailed accounts about their inhabitants, visitors, interlopers, intimates, and detractors. Living in and near the town for periods of time over the course of the nineteenth- and twentieth-centuries have been: French writer Marcel Proust, American art historian Bernard Berenson, German painter Paul Klee, Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, and American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. The town is known as the most affluent suburb of Florence. Also illustrative of historical layering is the Hotel Villa Aurora, just steps from the bus stop in Piazza Mino. Recently closed, the hotel was still in 2018 housing visitors to Fiesole.

Also illustrative of historical layering is the Hotel Villa Aurora, just steps from the bus stop in Piazza Mino. Recently closed, the hotel was still in 2018 housing visitors to Fiesole. Every character must re-assess and re-consider what they knew or thought they knew in 1944, what they know or think they know in 1989. The inevitable and irrefutable corollary, of course, follows as a question: What is the relationship between the historical record and a human being’s experienced life? This is the question The Contessa’s Easel explores.

Every character must re-assess and re-consider what they knew or thought they knew in 1944, what they know or think they know in 1989. The inevitable and irrefutable corollary, of course, follows as a question: What is the relationship between the historical record and a human being’s experienced life? This is the question The Contessa’s Easel explores.

At midnight on a doom-laden Hallowe’en three young lasses sit round the hearth in the West Tower, gazing into the flames trying to divine their future. From this fortress perched high on a rocky outcrop on the banks of the River Tyne, accessible only by a narrow farm track, the powerful Hepburn family, the Earls of Bothwell, controlled the lands of East Lothian. Though now a ruin, this hidden gem retains many features still recognisable enough to fire the novelist’s imagination. In the Great Hall, the earls would host grand banquets prepared in the vaulted kitchen underneath where scullions would turn spits over huge fires; children would scamper up and down the turnpike staircases of the three towers, and prisoners would languish in the two pit prisons or oubliettes – one of which is said to have contained George Wishart after his arrest. What must it have been like to have been lowered down into a pit and left in complete darkness on a freezing winter’s night?

At midnight on a doom-laden Hallowe’en three young lasses sit round the hearth in the West Tower, gazing into the flames trying to divine their future. From this fortress perched high on a rocky outcrop on the banks of the River Tyne, accessible only by a narrow farm track, the powerful Hepburn family, the Earls of Bothwell, controlled the lands of East Lothian. Though now a ruin, this hidden gem retains many features still recognisable enough to fire the novelist’s imagination. In the Great Hall, the earls would host grand banquets prepared in the vaulted kitchen underneath where scullions would turn spits over huge fires; children would scamper up and down the turnpike staircases of the three towers, and prisoners would languish in the two pit prisons or oubliettes – one of which is said to have contained George Wishart after his arrest. What must it have been like to have been lowered down into a pit and left in complete darkness on a freezing winter’s night? Marie Macpherson hails from from the historic town of Musselburgh, six miles from the Scottish capital Edinburgh, but left the Honest Toun to study Russian at Strathclyde University. She spent a year in the former Soviet Union to research her PhD thesis on the 19th century Russian writer, Mikhail Lermontov, said to be descended from the poet and seer, Thomas the Rhymer.

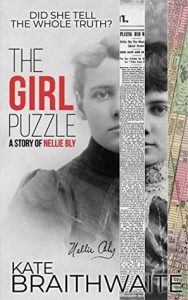

Marie Macpherson hails from from the historic town of Musselburgh, six miles from the Scottish capital Edinburgh, but left the Honest Toun to study Russian at Strathclyde University. She spent a year in the former Soviet Union to research her PhD thesis on the 19th century Russian writer, Mikhail Lermontov, said to be descended from the poet and seer, Thomas the Rhymer. The cover and title of this novel are worth thinking about before one opens the book itself. The author is telling us that at one level it is historical fiction, a tale told about a past epoch and how people lived then; at another, it is a story of someone’s life but not a biography. It is a story: the author’s interpretation of what happened to Nellie Bly. Who in turn was not only Nellie Bly but Elizabeth Cochrane, a young woman shaped by the lamentable circumstances of her parents’ life – which she is determined to overcome. The puzzle starts here, but is quickly forgotten because the author’s lucid prose and excellent characterisation means that one falls into the events of Nellie Bly’s life as if they were happening for the first time now.

The cover and title of this novel are worth thinking about before one opens the book itself. The author is telling us that at one level it is historical fiction, a tale told about a past epoch and how people lived then; at another, it is a story of someone’s life but not a biography. It is a story: the author’s interpretation of what happened to Nellie Bly. Who in turn was not only Nellie Bly but Elizabeth Cochrane, a young woman shaped by the lamentable circumstances of her parents’ life – which she is determined to overcome. The puzzle starts here, but is quickly forgotten because the author’s lucid prose and excellent characterisation means that one falls into the events of Nellie Bly’s life as if they were happening for the first time now.