Secondary and Minor Characters in Historical Crime Fictional

Secondary and minor characters help to establish the main character’s personality and develop the storyline in any fiction genre. In historical crime fiction they are also a useful means of conveying information about the epoch and location. This means no matter how lowly your minor characters need to be more than walk-on players in costume. To achieve this, ensure they have identifiable personalities, strengths, foibles or flaws that readers can relate to, so what they say and do is more meaningful.

If you are using a secondary character to provide a motive for a crime or to show what happens to your protagonist(s), that person’s agenda needs to be evident. This means creating a biography or backstory for all your characters at the planning stage, and ensuring they reflect the lifestyle, morals or zeitgeist of the period. Fiction requires readers to suspend disbelief, to engage in another world, to fear for, empathise or sympathise with the protagonist, and this is where your supporting cast play an important role. They not only demonstrate what life was like then, they show what was considered right and wrong, and therefore why your hero is special and the villain so reprehensible.

Golden age crime writers often included the victim’s ill-treatment of relatives and servants to show what may have led to their death, and why there is more than one suspect. This required creating backstories for all the suspects and using those details to feed in clues but without deviating too far from the main thrust of the story. Readers want to know why someone turns a blind eye to the crime; why someone refuse to help the authorities; or why a neighbour, for example, fabricates evidence.

As to the villain – a crime story or thriller becomes a lot deeper when the kindness of strangers highlights the vicious nature of the baddie. Readers turn pages to in crime stories to see how the wicked get caught; they turn them faster in thrillers if they not only fear for the main character but also for the little people caught up in the drama. Very few people in real life are wholly good or bad, though. A fact skilful authors exploit to the maximum. Each suspect, be it cozy crime or a blood bath, should be capable of committing the crime given enough reason.

Whatever the epoch, minor characters’ upbringing and moral codes inform their actions, which can be included in well-chosen cameo scenes. The gentler side of the wrong-doer or the darker side of the victim or detective can be demonstrated by showing how they interact in these situations. Whether you use these scenes as red herrings to mislead readers or to emphasise clues as to who-dunnit, secondary characters should be interesting and complex, and minor characters there in the story for a specific reason. To be sure of this, create mini-biographies at the planning stage. Whether you actually use these backstories (very sparingly) or not, the fact that you have thought about why Milly won’t tell, why Old Tom is digging the master’s garden at eighty, or why a senior officer overlooks a terrible error of judgment, will enrich your tale and leaven the plot.

Here are two examples of how I have used a secondary and minor characters to establish a seventeenth-century anti-hero’s complex identity and to provide information on the setting and location of a twentieth century wartime murder mystery. Each scene is directly relevant to the plot and includes details on the historic background.

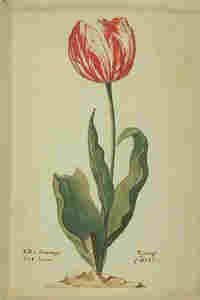

The first extract is from Book 1 of The Chosen Man Trilogy. It is 1635, charismatic Genoese merchant Ludovico da Portovenere (Ludo) is engaged in a conspiracy to inflate the tulip market in what became known as tulip fever. At this stage, readers are not sure whether Ludo is to be trusted, whether he’s a goodie or a baddie. How he handles his young Spanish servant Marcos here suggests he exploits people for his own ends. The dialogue also carries vital details about ‘tulipmania’.

The first extract is from Book 1 of The Chosen Man Trilogy. It is 1635, charismatic Genoese merchant Ludovico da Portovenere (Ludo) is engaged in a conspiracy to inflate the tulip market in what became known as tulip fever. At this stage, readers are not sure whether Ludo is to be trusted, whether he’s a goodie or a baddie. How he handles his young Spanish servant Marcos here suggests he exploits people for his own ends. The dialogue also carries vital details about ‘tulipmania’.

Ludo’s lodgings, Amsterdam, 1635

Marcos rubbed at the heel of the shoe (he was cleaning) and without looking up, said, “Is it this selling that’s made you rich?”

“This selling? What selling? What are you saying boy?”

“It’s that I don’t exactly understand what you’re doing, sir.”

“And why do you need to understand? It’s none of your damned business. You only latched onto me as a means of finding your long-lost father, who you seem to have forgotten in the most unfilial manner.”

“That’s not true!” Marcos replied, hurt by the Italian’s tone. “It’s just that I want to learn and go back home with more than I came with – if I can’t find my father – and if what they say in the streets and taverns is true, that’s probably what’s going to happen. I want to go home rich.” He paused, regretting his words, “Richer than when I came,” he held up the shoe and turned it in the air for inspection, “so I was sort of wondering if perhaps you could let me have a loan, and I could buy some of what you have and sell it.”

“At a profit?”

“Oh, yes, that’s what I want to do – make a profit, like they talk about with these flowers. There’s hundreds of profit, they say, buying and selling your flowers.”

“‘Hundreds of profit’. Interesting concept. Are you going to embalm that piece of footwear or get my breakfast?”

“Oh, yes, sorry. There’s some bread from yesterday and some ham and some beer. Do you want some of that tea stuff?”

“That ‘tea stuff ’ is very expensive merchandise, show some respect.”

“Sorry. Do you?”

“Tea? No!”

Marcos busied himself in the kitchen area and picked up on the conversation he wanted to continue. “So, what I was thinking was ...”

“You want me to give you some bulbs so you can sell them and make hundreds of profit. And what will you give me in return?”

Marcos put a plate and a tankard down in front of the merchant and looked him in the eye, confused, “I don’t understand? What do I have to give you in return?”

Ludo sighed, looked at the warm, flat beer and settled back in his chair. “I think we had better begin with the basics of commerce. Cut me some of that bread and ham – but wash your hands first.”

(. . .) Marcos listened intently then said, “But why are these Dutchies buying things they’ve never seen and don’t need with money they haven’t got.”

“Explain,” said Ludo.

“Well, last night I was in the Red Cockerel and a lot of odd bods were sneaking into a room at the back, so I sneaked in too. They were having some sort of sale, but there were only a few of those plant things you’ve got in your case. The rest were signing bits of paper for flowers that didn’t exist. Least ways I didn’t see them, I s’pose they might be in people’s gardens.”

Ludo raised an eyebrow, “Well done. And how exactly did you follow these transactions? You said you had no Dutch.”

Marcos lifted one of his master boots and started to shine it with the linen towel. “Numbers are numbers, not difficult to guess. These are the softest boots I’ve ever touched.”

“And these men, who would you say they were?”

“Oh, that’s easy, butchers and bakers, they still had their aprons on. Some toffs as well. I followed one in like his servant. He didn’t notice. There were a couple of gents like the one you were with a few days ago. The man that owns the Cockerel was running the show. They have a special code for when they go into the room – they go ‘cock-a-doodle-do’. Sounds really stupid. I bet if you want to do business in the Golden Lion you have to go ‘grrrrr’.”

Ludo sat and stared at the boy for a moment then said, “The answer is ‘yes’. I will let you have a loan and some goods at rock bottom prices – and you are going to make us hundreds of profit with a cock-a-doodle-do.” Then he got up and went into his room to wash, saying, “And in the meantime I’m going to make thousands of profit with numbers on bits of paper.”

There is a hint here that Ludo is not all bad; he is trying to help Marcos improve his status or at least educate him. From this point on, I wanted readers to have personal opinions on what Ludo is doing and why, for them to be more actively engaged in his wrong-doing and, later, fear for him when he tries to escape his evil antagonist. I was also using a secondary character to show how and why ordinary men and women traded tulip bulbs at outrageous prices, and how some (including the feisty heroine of the story) fell victim to Ludo’s wicked charm, and suffered for it.

The second scene comes from my new Bob Robbins Home Front Mystery, Courting Danger (to be released March, 2021 – this is the working cover only). Here, I am using two minor characters to tell readers about two suspects in a murder enquiry, and show how the wartime restrictions were affecting ordinary people.

Cornwall, England, 1943.

Shem Placket and his wife Violet were obliged to vacate their farmhouse home when the local landowner Charles Kittoe and his sophisticated wife moved to Cornwall during the blitz. The Kittoes have now left. Shem and Violet are discussing how this affects them, and whether the Kittoes are involved in the death of a local young doctor.

“They expect too much of you.” Mrs Placket tipped fluffy white potatoes into a dish and slapped on bright yellow butter.

“It works to our favour, my dear. Gives us more peace than most farm managers get.”

“Do you think we ought to say something?” Mrs Placket asked, removing her pinny before they sat down to eat.

“Say something about what? This smells good, Violet, where’s the meat?”

“Seek and ye shall find.” Violet ladled gravy over three types of root vegetable. “What I’m saying is, should we tell that police detective what we know?”

“If he comes asking, I might mention something. We don’t want to risk our place here, though, do we? Not at our age. You’ll have that fancy big kitchen to cook in again now.”

“Nothing wrong with the old range. Got to learn all new-fangled gas timings and settings and Lor’ knows what.”

Shem Placket looked at his wife: she had been pretty, once upon a time. “No point rockin’ the boat. They might let us have this cottage when I retire. No, if the police come knocking, I’ll tell what needs to be said. If they ask. Nothing more.”

Violet Placket met her husband’s eye, “But you know what’s happenin’ up in that cave.”

“I don’t for sure, Violet. Not for certain. But you know me: I speak when spoken to, and not before.”

“They could be taking pills or magic potions and acting out old rituals then lying spark out in the dark like they said they did when we were young’uns.”

“Far as I know it wasn’t breaking the law then, and if that’s still going on – well, it b’aint killed anyone yet.”

“It might have killed that young doctor. Why didn’t you tell me it was him in the pool?”

“Didn’t know it was. Don’t know as I’ve ever met the boy face to face. And we don’t know he was up to no good in that ol’ cave neither.”

“He spent enough time with Mrs Kittoe . . .”

Shem raised a calloused, warning hand. “That is enough, wife. If they ask . . .” he removed a woody stalk from between his front teeth, “you can tell them about Mrs K and her carryings on, but keep Mr Kittoe out of it or we’ll be looking for a shed to live in. If anyone’s been up to no good it’s her, in my opinion.” Despite his need to protect his family, Shem had a very Wesleyan attitude to life. “You understand what I’m saying?”

The trick in historical crime writing is to maximise the use of secondary and minor characters to provide information on the epoch and details on the crime(s).

Whether you are at the planning stage or into your first draft, write out a cast list and make a note next to each name to say what that character brings to the story.

Remember, in e.books it is harder to turn back to remind yourself who’s who, so make sure each person in your story is memorable and there for a reason.

Enjoy your writing! JGH

In my crime novel Mind the Killer I have used my in-depth knowledge of London’s transport system (having been a police officer for thirty-three years in the capital) to enhance a reader’s experience. Being able to visualise fictional events at real locations is something I enjoy when reading and writing as well. Mind the Killer not only has scenes at many London Underground stations but also some well-known landmarks such as St Paul’s Cathedral.

In my crime novel Mind the Killer I have used my in-depth knowledge of London’s transport system (having been a police officer for thirty-three years in the capital) to enhance a reader’s experience. Being able to visualise fictional events at real locations is something I enjoy when reading and writing as well. Mind the Killer not only has scenes at many London Underground stations but also some well-known landmarks such as St Paul’s Cathedral. Find Gary and his books – fact and fiction – on Amazon and other online books stores.

Find Gary and his books – fact and fiction – on Amazon and other online books stores.

While researching events in Britain during 1944, I came across a short comment made by someone on a history blog about how Churchill and Eisenhower met for an ultra-secret meeting at a private home on the east coast of Scotland in the month prior to D-Day.

While researching events in Britain during 1944, I came across a short comment made by someone on a history blog about how Churchill and Eisenhower met for an ultra-secret meeting at a private home on the east coast of Scotland in the month prior to D-Day.

The first extract is from Book 1 of The Chosen Man Trilogy. It is 1635, charismatic Genoese merchant Ludovico da Portovenere (Ludo) is engaged in a conspiracy to inflate the tulip market in what became known as tulip fever. At this stage, readers are not sure whether Ludo is to be trusted, whether he’s a goodie or a baddie. How he handles his young Spanish servant Marcos here suggests he exploits people for his own ends. The dialogue also carries vital details about ‘tulipmania’.

The first extract is from Book 1 of The Chosen Man Trilogy. It is 1635, charismatic Genoese merchant Ludovico da Portovenere (Ludo) is engaged in a conspiracy to inflate the tulip market in what became known as tulip fever. At this stage, readers are not sure whether Ludo is to be trusted, whether he’s a goodie or a baddie. How he handles his young Spanish servant Marcos here suggests he exploits people for his own ends. The dialogue also carries vital details about ‘tulipmania’.

In the opening scene of Vital Spark, Alex Allaway is driving along a coastal road, through a valley of summer corn on Maryland’s eastern shore. She’s thrilled to be returning home. She’s landed a job as a fisheries ecologist at a small marine station in her hometown of River Glen. River Glen is the epicenter of my new Chesapeake Tugboat Murders series. The village is located at the intersection of the fictional Glen River and the real Chesapeake Bay.

In the opening scene of Vital Spark, Alex Allaway is driving along a coastal road, through a valley of summer corn on Maryland’s eastern shore. She’s thrilled to be returning home. She’s landed a job as a fisheries ecologist at a small marine station in her hometown of River Glen. River Glen is the epicenter of my new Chesapeake Tugboat Murders series. The village is located at the intersection of the fictional Glen River and the real Chesapeake Bay.