An Author in Exile

As many of my readers know, after travelling widely we finally settled down in southern Spain. Without knowing it beforehand, we moved into a locally renowned area for breeders of Pura Raza Español horses (known in UK and USA as Andalusians, I think). It was an ideal spot for me, but after the death of the last of our horses (at the ripe old age of 27), we decided the time had come to move nearer family and urban conveniences such as shops.

For my husband, this has been a return to his home province of Andalucía. For me, this (possibly) final-final move means accepting my voluntary exile as a ‘foreign wife’ is a permanent situation. My lifestyle has been more Latin than British for a long time now, but I still think of North Devon as home. Although to be honest I’m an exile in England these days as well: people do things differently there.

In my experience, being a voluntary exile is a combination of exciting new challenges, learning a language, buying new types of food etc, mixed with occasional bouts of irritation, annoyance and nostalgia. For a writer, however, it has certain advantages. Seeing one’s surroundings with an objective eye leads to a deeper awareness of both culture and the natural environment, which in Spain are closely connected. In the province of Madrid summers are very hot and winters are bitterly cold. As in many other provinces, there is barely a day of springtime or autumn as the year moves from one extreme to the other. So it is with many people: warm, close friendships, or the literally cold shoulder.

From the kitchen window of our new home, I can see the mauve-shaded Sierra de Málaga, where the Moors of Al-Ándalus harvested snow to keep medicines cool. On the other side of the house, beyond a set of hills, lies the now densely crowded Costa del Sol. A coastline once prey to the Barbary corsairs featured in The Chosen Man Trilogy and my current work-in-progress, The Doomsong Voyage. Away from tourist hot-spots, though, it is easy to drift into time travel: pretend there’s no road nearby or enter a small pueblo bar serving local wine or cider and it could be any century at all.

Before coming to Spain, I was living on the Ligurian coast of Italy – hence Ludo da Portovenere (the charismatic rogue of The Chosen Man Trilogy). The Genoese coastline creeps into Ludo’s narrative when, as an involuntary exile, he reminisces about his childhood.

Before coming to Spain, I was living on the Ligurian coast of Italy – hence Ludo da Portovenere (the charismatic rogue of The Chosen Man Trilogy). The Genoese coastline creeps into Ludo’s narrative when, as an involuntary exile, he reminisces about his childhood.

On occasions I had to curb Ludo’s nostalgia to prevent his story becoming a travel brochure: Portovenere, or Porto Venere, is very picturesque. Once the site of a Roman temple to Venus, it was the perfect location to conclude Ludo’s wicked adventures in By Force of Circumstance. I know this because I wasn’t just visiting: I was living there, buying groceries, taking children to school, being part of Italian daily life. Unconsciously, or sub-consciously I was stashing away sights, sounds and anecdotes for future historical crime novels. Authors in exile notice how people behave and interact. We tuck away special moments and the kernels of raw stories like squirrels in autumn. This is how my contribution to the new anthology Historical Stories of Exile came about.

Many years ago, a dear friend told me how her Polish parents met and married in post-war London. Her grandmother had walked from Warsaw to the Bosphorus with two daughters, found a passage to Spain, then to London. It took them two whole years to find a safety – in a city being bombed every night. I thought at the time it merited a full-length novel, but as I have never been to Poland and lack even a basic grasp of the language I didn’t feel up to the task. Nonetheless, the family’s experience stayed in my mind and eventually formed the background to my Victory in Exile short story (details below). The narrative itself links into my WWII Bob Robbins Home Front Mysteries series. It also includes elements told me by my Dutch neighbour when we were living in the Hague back in the ’90s. Ultimately, however, Victory in Exile reflects the current tragedy of innocent refugees trying to find a safe haven in a world at war.

I have never accepted the idea that a work of fiction can be reduced to its author’s life, but autobiographical moments do creep in, especially those related to the emotions. Here’s a scene from my first historical crime novel The Empress Emerald as an example. In the extract, a newly married, naïve Cornish girl arrives at her new family home in Jerez. It is 1920 in the story, what happens is a fictionalised version of my own arrival in Puerto Santa Maria in the 1980s.

The driver stopped the car outside two vast doors, blackened with age and reinforced with iron. They reminded Davina of an illustration in one of her big picture books: Bluebeard’s castle. As if by some sinister magic, a door swung open. Alfonso ushered her into a fern-infested patio. It smelt dank and uninviting. She looked up and around her. The patio was open to the sky, but on all four sides above there were windows. She sensed watching eyes and lowered her gaze.

The autobiographical element ends there. But my experience of being a voluntary exile obviously informs my writing. I know what it is like not to speak the language, not to share commonly acknowledged values; what it is like to be gaped at because your appearance or style doesn’t fit with the locals. I’ve been living in Spain, on and off, for years but people still ask me where I am from. I try not to bristle, and can’t help thinking about what being an involuntary exile must be like for those who can never go home.

J.G. Harlond

Find the new short story anthology Historical Stories of Exile at: https://mybook.to/StoriesOfExile

If you enjoy action-adventure travel stories and historical fiction here are a couple recommendations for a thumping good read:

- The Imp of Eye series by Kristin Gleeson: The Imp of Eye | Universal Book Links Help You Find Books at Your Favorite Store! (books2read.com)

- Helen Hollick’s Sea Witch series, which features a likeable rogue hero named Jesamiah Acorne: https://viewauthor.at/HelenHollick

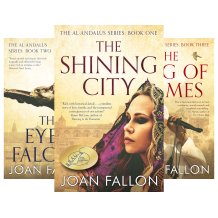

You can read about how my wicked hero Ludo da Portovenere creates mayhem in 17th Century Europe in three novels starting with The Chosen Man.

You can read about how my wicked hero Ludo da Portovenere creates mayhem in 17th Century Europe in three novels starting with The Chosen Man.

Each story is based on some surprising and lesser-known real events involving the Vatican and crowned heads of Europe during the Thirty Years War and the English Civil War. http://getbook.at/TheChosenMan

The Empress Emerald is available on: https://mybook.to/p6ZMzs

The Empress Emerald is available on: https://mybook.to/p6ZMzs

In Britain and Ireland, there was the added, critical risk of imminent invasion. It had happened in Poland and the Channel Islands, it could happen in Britain. The detail about the German U-boat surfacing off the Cornish coast to take on fresh water in Local Resistance was taken from a German sailor’s account. I didn’t invent that.

In Britain and Ireland, there was the added, critical risk of imminent invasion. It had happened in Poland and the Channel Islands, it could happen in Britain. The detail about the German U-boat surfacing off the Cornish coast to take on fresh water in Local Resistance was taken from a German sailor’s account. I didn’t invent that. How a Cornish fishing village uses its ancient smuggling tradition to evade rationing while preparing to defend their country when ‘Jerry’ landed forms the background to Local Resistance; how people as diverse as Land Army girls and cosmopolitan actors coped three years into the war underlies the shenanigans and criminal activities in Private Lives.

How a Cornish fishing village uses its ancient smuggling tradition to evade rationing while preparing to defend their country when ‘Jerry’ landed forms the background to Local Resistance; how people as diverse as Land Army girls and cosmopolitan actors coped three years into the war underlies the shenanigans and criminal activities in Private Lives.

It is 80 years now since Daphne du Maurier’s novel Rebecca was first released. Back in 1938, du Maurier’s publishers were nervous about the novel’s future, but the story has become a classic: a world-wide favourite, a play, a television series, even an iconic black and white movie. For a while, back in the 90s, new editions of du Maurier’s novels were hard to obtain, but with the recent film version of My Cousin Rachel she is very much back in the public eye.

It is 80 years now since Daphne du Maurier’s novel Rebecca was first released. Back in 1938, du Maurier’s publishers were nervous about the novel’s future, but the story has become a classic: a world-wide favourite, a play, a television series, even an iconic black and white movie. For a while, back in the 90s, new editions of du Maurier’s novels were hard to obtain, but with the recent film version of My Cousin Rachel she is very much back in the public eye. Big houses, full of private tragedies and secret histories, feature in many of her novels. Looking at photographs of Menabilly I wonder if that house stands as a metaphor for her fiction – as full of conflicting emotions, versions of the past and fantasies as the house on the strand. Such thoughts and ideas are only suggested, it is up to each reader to interpret them of course, and as in real life we interpret them according to our own way of thinking and personal experiences. Readers bring their own baggage to any book.

Big houses, full of private tragedies and secret histories, feature in many of her novels. Looking at photographs of Menabilly I wonder if that house stands as a metaphor for her fiction – as full of conflicting emotions, versions of the past and fantasies as the house on the strand. Such thoughts and ideas are only suggested, it is up to each reader to interpret them of course, and as in real life we interpret them according to our own way of thinking and personal experiences. Readers bring their own baggage to any book. This post first appeared in the Discovering Diamonds blog:

This post first appeared in the Discovering Diamonds blog:  Healthy, well-trained horses entered in modern long-distance races, sometimes called endurance races (for a very good reason) can cover up to 100 miles in a day. The favoured breed is the Arabian, but while the type of breed matters, it’s the training that is important. Each mount has to be prepared for these distances over a long period of time, and this includes getting used to eating hard fodder at different times of the day, which many horses do not or will not do.

Healthy, well-trained horses entered in modern long-distance races, sometimes called endurance races (for a very good reason) can cover up to 100 miles in a day. The favoured breed is the Arabian, but while the type of breed matters, it’s the training that is important. Each mount has to be prepared for these distances over a long period of time, and this includes getting used to eating hard fodder at different times of the day, which many horses do not or will not do. A final word: these blog posts are written from my personal experience of a life-time caring for and training horses. If you go to other on-line sources you may find conflicting or differing information.

A final word: these blog posts are written from my personal experience of a life-time caring for and training horses. If you go to other on-line sources you may find conflicting or differing information. The sheik was seated on cushions in a high-ceilinged room. There were no intricate tiles such as those of the Arab homes Ludo knew in North Africa, only brightly coloured wall-hangings and mats, and on a low oblong table a large patchwork cloth.

The sheik was seated on cushions in a high-ceilinged room. There were no intricate tiles such as those of the Arab homes Ludo knew in North Africa, only brightly coloured wall-hangings and mats, and on a low oblong table a large patchwork cloth.

It was the summer of 2001. I picked up a leaflet about an exhibition that was to be held in the museum at Madinat al-Zahra. It was entitled The Splendour of the

It was the summer of 2001. I picked up a leaflet about an exhibition that was to be held in the museum at Madinat al-Zahra. It was entitled The Splendour of the  Once the seat of power had been removed from Madinat al-Zahra, the city went into decline. The wealthy citizens left, quickly followed by the artisans, builders, merchants and local businessmen. Its beautiful buildings were looted and stripped of their treasures and the buildings were destroyed to provide materials for other uses. Today you can find artefacts from the city in Málaga, Granada, and elsewhere.

Once the seat of power had been removed from Madinat al-Zahra, the city went into decline. The wealthy citizens left, quickly followed by the artisans, builders, merchants and local businessmen. Its beautiful buildings were looted and stripped of their treasures and the buildings were destroyed to provide materials for other uses. Today you can find artefacts from the city in Málaga, Granada, and elsewhere. There are two sets of Dorothy Dunnett’s two historical novel series on my bookshelves, plus two copies of King Hereafter: a few are hardbacks the rest are now dry, cracked-spine paperbacks, whose pages are so yellow and print so small that I struggle to read them – but I still do. I’ve bought a few replacements over the past forty years, but somehow can’t bring myself to throw or even give away the originals. The other curious thing about these old books is something very modern. Without strapping any box to my head or standing in any man-made cubicle wearing black goggles they produce a form of virtual reality. Just by looking at a title I can see scenes. Stills and moving images hang in the air: a joyous youth riding an ostrich, the same man now older rides a silken-hide camel; a little boy with sturdy legs runs through apricots drying on a rooftop; a vast eagle swoops across a snowy waste onto an arm; a mad, brave youth runs across moving oars and marries a woman with ‘spawn-like’ eyes . . .

There are two sets of Dorothy Dunnett’s two historical novel series on my bookshelves, plus two copies of King Hereafter: a few are hardbacks the rest are now dry, cracked-spine paperbacks, whose pages are so yellow and print so small that I struggle to read them – but I still do. I’ve bought a few replacements over the past forty years, but somehow can’t bring myself to throw or even give away the originals. The other curious thing about these old books is something very modern. Without strapping any box to my head or standing in any man-made cubicle wearing black goggles they produce a form of virtual reality. Just by looking at a title I can see scenes. Stills and moving images hang in the air: a joyous youth riding an ostrich, the same man now older rides a silken-hide camel; a little boy with sturdy legs runs through apricots drying on a rooftop; a vast eagle swoops across a snowy waste onto an arm; a mad, brave youth runs across moving oars and marries a woman with ‘spawn-like’ eyes . . . If you recognise any of these scenes you probably qualify as a Dorothy Dunnett fan, and are very likely a ‘historical fiction junkie’. That’s what I was told Dunnett fans were a few years ago. There are currently three Facebook groups for Dunnett fans that I know of. I dip in now and again and am always rewarded by some insight into a bit of history or details on one of the many locations. The news on one today is from a student in Australia who is writing her MA dissertation on Dunnett.

If you recognise any of these scenes you probably qualify as a Dorothy Dunnett fan, and are very likely a ‘historical fiction junkie’. That’s what I was told Dunnett fans were a few years ago. There are currently three Facebook groups for Dunnett fans that I know of. I dip in now and again and am always rewarded by some insight into a bit of history or details on one of the many locations. The news on one today is from a student in Australia who is writing her MA dissertation on Dunnett.