Beyond the Fields We Know

‘Whatever I write, I start with the setting . . . ‘

How and why a writer can be inspired by a landscape or location by Marian L Thorpe, author of the Empire’s Legacy Trilogy.

One of my favourite walks is along part of a long-distance path that follows the route of a Roman road that probably follows an even older track. At its North Sea end, wooden henges stood. On either side of the section I walk most frequently, Bronze Age barrows rise from the fields. The ruins of Roman villas lie under the soil not far from it; the moot hill of the Saxon hundred it crosses is believed to be by its side. In The King of Elfland’s Daughter, Lord Dunsany described fairyland as lying ‘beyond the fields we know.’ I don’t write about fairyland, but I do write about a world that lies lightly on a palimpsest of our real, historic world.

Whatever I write, I start with the setting. Stories emerge from landscapes for me, and even when they are complete fiction their settings are strongly based on a real place. Whether it’s verse—the first work I had accepted for publication as an adult—or my short stories, or my novels, they are all rooted in and inseparable from the physical world in which they are set.

I had a rural childhood of the sort almost unimaginable today. I grew up over 50 years ago, roaming fields and woods and lanes on foot or on my bike, often alone. I watched the progression of wildflowers over the summer; I watched planting and harvest.

I had a rural childhood of the sort almost unimaginable today. I grew up over 50 years ago, roaming fields and woods and lanes on foot or on my bike, often alone. I watched the progression of wildflowers over the summer; I watched planting and harvest.

I learned to identify trees and birds and wildlife, and understand to some extent the landscape in which I lived and the forces, human and natural, that had shaped it. The theme of the first novel I ever began, at seventeen, is the relationship between a man and the land, the deep, hard-fought and hard-won connection between the two—and that’s still a theme in my Empire’s Legacy series.

The books I loved to read as a child were books that were firmly placed in their landscapes. Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons series; The Wind in the Willows. Puck of Pook’s Hill. Rosemary Sutcliffe, and many, many more. Books where landscape is a character, in a way. I also grew up in a family where history was important. It was discussed, my interest encouraged. My father’s love was Tudor/Plantagenet history; mine evolved into late classical/early medieval.

In my twenties and thirties my husband and I travelled as extensively as we could, not to cities but to the footpaths and trails of almost every country and county of the UK and throughout North America. I soaked up landscape, I soaked up history, and I fell deeply in love with the concept of landscape history. (Thanks, Time Team!) So when I began to write Empire’s Daughter, the first book in the Empire’s Legacy series, I started with a landscape: the coast of Anglesey. I saw it, and then I began to populate it with characters and a society.

The series isn’t set in the real world, but neither is it truly a fantasy world. There are no variations from the laws of physics or nature, only (barely) a fantasy geography. There are no fae or otherworldly creatures, only the flora and fauna of northern and central Europe.

The series isn’t set in the real world, but neither is it truly a fantasy world. There are no variations from the laws of physics or nature, only (barely) a fantasy geography. There are no fae or otherworldly creatures, only the flora and fauna of northern and central Europe.

Every place in the entire series has a real-life inspiration, and I’ve been to most of them. (If I haven’t, I’ve substituted a place I have been, in a similar ecological/geographic niche.)

The reasons for this are many, and varied. As someone who was, for a chunk of her life, a biological scientist, and has been for all her life an amateur field naturalist, I am annoyed beyond words with unreal worlds whose ecologies don’t work. So that’s one reason, but not the major one. The books are set in an analogue world, but it’s one that for many people will be both recognizable and familiar—and that was done on purpose. Because my books explore questions of societal and socio-sexual structures and expectations, because they are more concerned with questions of philosophy and morality and politics than battles, I didn’t want to add another layer of worldbuilding to the mix. It would have been a distraction, another thing for the reader to have to think about and absorb.

In the first two books my main character Lena never leaves the known world, one based entirely on the UK both geographically and historically. There’s a Wall, there’s a country north of the Wall, and these two countries are long-term enemies. The country north of the Wall has a province that sometimes belongs to them, and sometimes to the seafaring people from even further north. Even the battles are based on real ones: Stanford Bridge, the Battle of Maldon. For me, and for anyone who learned British history in any detail, this all should feel familiar – and that’s what I wanted: to place, in a familiar setting, a story that challenges a number of societal structures.

The third reason for the settings of my books is simple: I draw heavily on my own experiences in the descriptions of my characters’ interactions with their environments. I’ve been pelted by hailstones on a mountainside. I’ve slipped on scree; I’ve walked on dusty, arid plains, climbed up waterfalls (not quite as terrifying as the one Lena does), camped in the cold and wet and lived (albeit briefly) in primitive wooden huts. It’s easier to write about real experiences than it is to make them up.

Mix the idea of a world that lies beyond the fields we know, add the discovered and undiscovered history that lies beneath the fields we know, throw in a strong seasoning of love for landscape and nature, a dash of the belief that we are shaped by the places we love, and bake that all in the mind of a writer—and you have the genesis of the world I created in Empire’s Legacy. © Marian L Thorpe 2023

Find out more about Marian L Thorpe’s books on: marianlthorpe.com

Many generations past, the great empire from the east left Lena’s country to its own defences. Now invasion threatens…and to save their land, women must learn the skills of war.

Many generations past, the great empire from the east left Lena’s country to its own defences. Now invasion threatens…and to save their land, women must learn the skills of war.

But in a world reminiscent of Britain after the fall of Rome, only men fight; women farm and fish. Lena’s choice to answer her leader’s call to arms separates her from her lover Maya, beginning her journey of exploration: a journey of body, mind and heart.

Read my review of Empire’s Daughter on Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/54687565-empire-s-daughter

Find Marian’s books on: https://books2read.com/marianlthorpe

Ruth Downie was impelled to write after a visit to Hadrian’s Wall. What inspired her, though, was what was not there: tombstones for the women who lived with and worked for the occupying Romans.

Ruth Downie was impelled to write after a visit to Hadrian’s Wall. What inspired her, though, was what was not there: tombstones for the women who lived with and worked for the occupying Romans. Elizabeth Freemantle tells of her visit to the Elizabethan house Hardwicke Hall in Derbyshire, which inspired The Girl in the Glass Tower: ‘The place is perched on a hill surveying the surrounding countryside and in my mind it became a glorious prison (for the tragic royal girl, Arbella Stuart)’. Had she visited on another day would the way the daylight lit the walls or her inner feelings have resulted in a quite different novel?

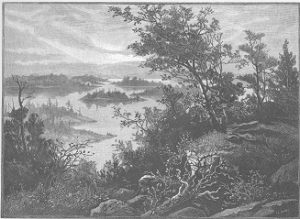

Elizabeth Freemantle tells of her visit to the Elizabethan house Hardwicke Hall in Derbyshire, which inspired The Girl in the Glass Tower: ‘The place is perched on a hill surveying the surrounding countryside and in my mind it became a glorious prison (for the tragic royal girl, Arbella Stuart)’. Had she visited on another day would the way the daylight lit the walls or her inner feelings have resulted in a quite different novel? Janet Kellough’s books about the saddlebag preacher Thaddeus Lewis set in nineteenth century Upper Canada (now Ontario) involved exploring the regions he covered, the northern shores of the Great Lakes, even the backcountry.

Janet Kellough’s books about the saddlebag preacher Thaddeus Lewis set in nineteenth century Upper Canada (now Ontario) involved exploring the regions he covered, the northern shores of the Great Lakes, even the backcountry.