Writing about real diamonds in historical fiction

Once upon a time, I had gap year job in a jewellery and antique shop. I was taken to their workshop to see how jewels were cut and set, and gradually learned what sort of antiques sold to what sort of customer. It was a pleasant job, but not what I wanted to do for the rest of my life. Looking back, however, much of what I learned then has come in very handy for my historical fiction.

Budding authors are advised to write what they know: my first novel, The Magpie, subsequently re-written as The Empress Emerald, is about Leo Kazan, a young man in colonial Bombay who has a fascination for all things shiny. I had a basic knowledge of the gems, and what I knew about India during the Raj came from tales of a great uncle who loved his time in India. In writing this novel – and without giving it any thought – I was combining the far away and long ago with personal experience. A technique I extended for The Chosen Man trilogy, drawing on my time living in Italy, the Netherlands and Spain with events that happened centuries ago.

While preparing for my new release, A Turning Wind, (Book 2 in The Chosen Man trilogy), I came across the writing of the French merchant-explorer Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (1605-1689). In a spell-binding account of how diamonds were mined in the Golconda region of India he quotes an account supposedly written by Marco Polo of how diamonds were found and traded in the area centuries before. It was too good not to use so I wove it into the opening scene of A Turning Wind, it also sets the scene for what is to come later perfectly.

Goa, India, September 1639

It was a ramshackle affair for such valuable goods. A makeshift marketplace created out of crimson and brightly striped awnings. Lengths of scarlet, orange, turquoise, purple and blue formed curtains between trees; sheltering the splendid commodities from the late summer sun. Vendors were still laying out their wares when Ludo arrived: gems and trinkets in copper and gold, ivory combs and bangles, shimmering sari silk and embroidered fringed shawls, all transported from one coast of India to the other on heads and shoulders. The costly cargo had passed through the famous alluvial diamond valleys of Golconda, the human caravan collecting ever more precious gems along the way – a cargo now watched over by guards with arm muscles that rippled ‘beware’ and vicious knives tucked in wide belts.

Curious, colourful, magnificent . . . everything Ludo had hoped for. He was delighted. Yet, wandering among the displays, he began to wonder why he had come – what, apart from uncut diamonds, he was actually seeking.

As he finished his first circuit, a white bullock ambled in pulling a cart laden with clay flagons. Happily over-paying an urchin for a drink of water then returning the cup, Ludo strolled back among the folding tables, trestles and floor mats, this time stopping to examine a miniature chest of drawers decorated with inlaid mother-of-pearl for women’s trinkets. It was pretty, but no, not special enough to add to his ship’s cargo. Moving on, he encountered an awkward Englishman dabbing at his forehead with a sodden handkerchief. The pink-faced sahib was struggling to keep up with an Indian agent’s heavily accented sales patter without losing his cherished dignity.

“Let me tell you how they are found,” the Goan agent was saying as he ran a hand seductively through a wide lacquered bowl of uncut diamonds. “When it rains, water rushes down the mountains, taking these precious stones with it and leaving them trapped at the bottom of gorges and in caverns. When the dry season comes and there is not one drop of water to be had, when the heat is enough to kill an Englishman as he walks from his door, brave men risk their lives to collect the stones. But they must go where wild serpents thrive. Venomous serpents and vast – serpents that crush and swallow men whole . . .”

Ludo shuddered along with the Englishman: snakes were another of the reasons he had made no attempt to travel inland during his stay in Goa.

“. . . but these diamonds are precious not only for the means by which they are obtained, not only for their special rarity, but for their quality. Look, sahib, see how fine they are, how they bring light into our lives. Each one is perfect, flawless . . .”

The Englishman put a forefinger in the bowl and peered at a stone the size of a sparrow’s egg, then at another the shape and form of a woman’s fingernail. The Goan agent took his hand and placed an uncut stone in the sweating palm then exchanged it for a cushion-cut diamond ring magicked from among his robes saying quietly, “This is not for everyone to know, sahib, but I should tell you, there may not be many more of these diamonds. Each year there are fewer. It is said the serpents now eat them to preserve their heritage.”

Ludo swallowed a grin and gestured with a hand to attract the agent’s attention. Half-convinced, half-enthralled, and knowingly walking into an enticement worthy of his own invention, Ludo stepped forward and cocked his head to one side enquiringly. The agent retrieved the ring from the Englishman and put it in Ludo’s open palm then whisked a heart-shaped ruby from thin air and put it next to the ring.

Ludo’s hand was broad but there was barely room for the two wonderful gemstones. The agent picked the ring from Ludo’s hand, leaving only the ruby to burn through his palm in the warm light of the coloured awnings.

“A gem worthy of a queen, sahib,” the agent murmured.

“Worthy of a queen . . . it is indeed,” Ludo murmured. This was what he wanted: this ruby. “But it is too much for a humble merchant such as me.”

“No, sahib, this ruby is for you. This is what you seek.”

Ludo shot him a surprised glance. The agent’s expression was open, generous, but two black-bead eyes under a startlingly white turban bore into him, hypnotising him, holding his gaze.

“You must know, sahib, a ruby of this quality has such virtues from the Sun that a man living in ignorance or consumed by sin, or pursued by mortal enemies, is saved by its wearing. When stones such as this are found they are named: this is ‘Rani Saahasi’. There is no perfect translation that I know in Portuguese: in English you could call it ‘Queen of Courage’.

Ludo forced himself to look away, shook his head to clear his vision and pulled himself back to the multi-coloured market place. But his fingers clenched the ruby of their own accord: the stone, as red as pomegranate seeds, as cool as the waters of Kashmir, sang in his palm. He had to have it.

“No,” he said. “No, I cannot risk my small income on a bauble such as this.”

The Englishman’s jaw dropped. Ludo willed him to move away, not wanting to risk haggling against the flushed-faced mister as well. The Englishman stayed exactly where he was.

Reluctantly, Ludo held out the ruby saying, “I seek smaller, uncut gems . . .” As he spoke a set of long-nailed, hairy fingers plucked the stone from his palm and the thief escaped round the trunk of the nearest tree.

A troop of other practised thieves appeared above, peering with the faces of buffoons between the different coloured awnings then scrambling helter-skelter from branches or shimmying like circus performers down supporting wooden props. The Goan agent screeched not unlike the unwanted visitors and grabbed the corners of his open cloth on the low table behind him, hugging the rapid sack to his bony chest so no more of his valuable goods could be taken. Suddenly there was a commotion around the bullock cart carrying water; a thief had upturned the clay cups and made off with a jug, carrying it awkwardly on three legs for she had a baby on her back. Her sister, meanwhile, discovered a display of brass incense holders and bells. Seizing as many as she could, she began to juggle; the bells ringing into the air then clanging to the soft mud beneath her feet. Then up went a candlestick, and then another and another, caught by one cousin and tossed to an uncle who, brandishing it as trophy, bared his teeth at the buyers and headed for home.

But as he went, more of his clan arrived, targeting push-carts, floor mats and head-rolls; some stealing arm bangles and pushing them up their thin, hairy arms before running back up the tree trunks into the branches and awnings, or jumping on tables, scattering wares that had crossed perilous oceans and scorching plains to be brought undamaged, intact across mountains and marshes down to Goa.

Ludo started to laugh at the shock and surprise of the invasion, then stopped as if the scene were frozen in time when the ruby he so coveted dropped to his feet from above.

“Choke on it, choke on it!” the monkey cursed, for it was inedible and he did not want it.

Slowly, slowly, hardly believing his luck, Ludo bent to pick up the gem. His right hand closed over it and it was his.

But it was not.

He started to walk out of the covered square, but his legs would not move. The ruby held him to the spot, telling him perhaps that a man living in ignorance or consumed by sin, or worse – pursued by a mortal enemy – is saved by its wearing. Ludo did not believe he was consumed by sin or that he lived in a state of ignorance, but he was pursued by enemies, one, possibly two, or even three if you counted the ridiculous Count Hawk – but he was no thief. No common thief, anyway.

***

‘Write about what you know’ and what you pick up along the way . . . My research has taken me down all manner of exotic rabbit holes, and (reported) truth can be much stranger than fiction. Quoting Marco Polo again, Tavernier explains how diamond gatherers supposedly avoided serpents to harvest precious stones:

“Now it is so happens that these mountains are inhabited by a great many white eagles, which prey on the serpents. When these eagles spy the flesh (raw meat men have flung into the valley) lying at the bottom of the valley, down they swoop and seize the lumps and carry them off. The men observe attentively where the eagles go, and as soon as they see that a bird has alighted and has swallowed the flesh, they rush to the spot as fast as they can. (…) When eagles eat the flesh, they also eat − that is, they swallow − the diamonds. Then at night, when the eagle comes back, it deposits the diamonds it has swallowed with its droppings. So men come and collect these droppings, and there they find diamonds in plenty.”

‘Diamonds in plenty’ – at seventeen I couldn’t see a future in them; now I cannot imagine how at least two of my novels could have been written without them.

©J.G. Harlond

This post was written for Helen Hollick’s Discovering Diamonds blog. You can read a review of ‘A Turning Wind’ on: https://discoveringdiamonds.blogspot.com/search?q=A+Turning+Wind

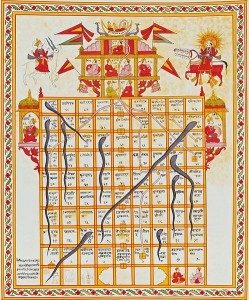

The sheik was seated on cushions in a high-ceilinged room. There were no intricate tiles such as those of the Arab homes Ludo knew in North Africa, only brightly coloured wall-hangings and mats, and on a low oblong table a large patchwork cloth.

The sheik was seated on cushions in a high-ceilinged room. There were no intricate tiles such as those of the Arab homes Ludo knew in North Africa, only brightly coloured wall-hangings and mats, and on a low oblong table a large patchwork cloth. Ruth Downie was impelled to write after a visit to Hadrian’s Wall. What inspired her, though, was what was not there: tombstones for the women who lived with and worked for the occupying Romans.

Ruth Downie was impelled to write after a visit to Hadrian’s Wall. What inspired her, though, was what was not there: tombstones for the women who lived with and worked for the occupying Romans. Elizabeth Freemantle tells of her visit to the Elizabethan house Hardwicke Hall in Derbyshire, which inspired The Girl in the Glass Tower: ‘The place is perched on a hill surveying the surrounding countryside and in my mind it became a glorious prison (for the tragic royal girl, Arbella Stuart)’. Had she visited on another day would the way the daylight lit the walls or her inner feelings have resulted in a quite different novel?

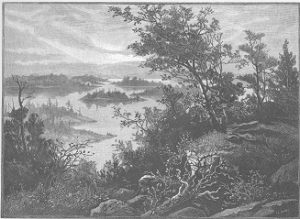

Elizabeth Freemantle tells of her visit to the Elizabethan house Hardwicke Hall in Derbyshire, which inspired The Girl in the Glass Tower: ‘The place is perched on a hill surveying the surrounding countryside and in my mind it became a glorious prison (for the tragic royal girl, Arbella Stuart)’. Had she visited on another day would the way the daylight lit the walls or her inner feelings have resulted in a quite different novel? Janet Kellough’s books about the saddlebag preacher Thaddeus Lewis set in nineteenth century Upper Canada (now Ontario) involved exploring the regions he covered, the northern shores of the Great Lakes, even the backcountry.

Janet Kellough’s books about the saddlebag preacher Thaddeus Lewis set in nineteenth century Upper Canada (now Ontario) involved exploring the regions he covered, the northern shores of the Great Lakes, even the backcountry.