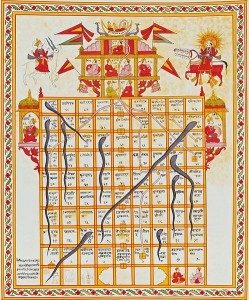

Themes in fiction can be subtle or more evident, sometimes, I find, they creep in while the book is a work-in-progress. This happened with the ‘snakes and ladders’ motif in the third story in The Chosen Man Trilogy. I came across the origins of the game while researching the background to By Force of Circumstance and it fitted what was happening to the wily, unreliable Ludo da Portovenere so perfectly I knew I had to include it in the narrative.

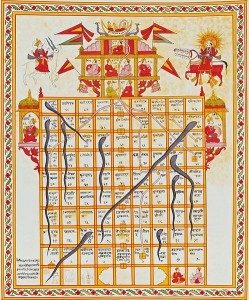

There are various theories and dates for how the game ‘snakes and ladders’ came about, but its origins are ancient and almost certainly ancient Asian. Originally called Mokshapat it was played with cowrie shells and dices. The ladders represented virtues, the snakes indicated vices, and the game demonstrated how good deeds take people to heaven and evil to the cycle of re-birth. An early version was devised or described by the 13th century poet Gyandev, but apart from its original intrinsic meaning, which has been lost, the game has undergone few modifications. The underlying meaning remained the same until it reached the west, where the more philosophical and didactic meaning was condensed to the chance and risk element of landing on a snake and slithering down to start all over again.

Snakes and ladders was played in India as one of many board and dice games, including pachisi (modern day Ludo), where it was known as moksha patam or vaikunthapaali or paramapada sopaanam, meaning the ‘ladder to salvation’ and emphasizing the role of fate or karma. A Jain version, Gyanbazi, has been dated back to the 16th century: a version called Leela reflects the Hindu concept of ‘consciousness’ in everyday life.

I came upon all this as I was reading and researching the historical background for my second story in The Chosen Man trilogy, which opens in 17th century Portuguese Goa. The original, ancient game fitted so perfectly with the story it became one of the main themes – the wily, unreliable Ludo is trying to make his fortune as a merchant, but he is also trying to find a meaning and focus for his life in general – so I knew I had to include it.

In the scene that follows, Ludo is on a trading voyage from Goa to Plymouth, his ship has anchored off an Omani beach and he has gone ashore to purchase pearls. Ludo sees two exquisite Arabian mares with their foals and finds his way to the local sheik intending to purchase them. Instead of the horse trading he’s expecting, however, he gets a lesson in destiny and desire.

*

1*

The sheik was seated on cushions in a high-ceilinged room. There were no intricate tiles such as those of the Arab homes Ludo knew in North Africa, only brightly coloured wall-hangings and mats, and on a low oblong table a large patchwork cloth.

The sheik was seated on cushions in a high-ceilinged room. There were no intricate tiles such as those of the Arab homes Ludo knew in North Africa, only brightly coloured wall-hangings and mats, and on a low oblong table a large patchwork cloth.

Ludo was led up to the sheik, who peered at him through unsmiling eyes then said, “You wish to take my joy from me and transport it across the world.”

“That is so, Excellency,” Ludo replied, wondering how he had divined where he wanted to take the mares having not thought it through himself.

The sheik stared at him until Ludo was forced to look away. Across the unfurnished room an eagle owl blinked, surprised perhaps to see a stranger. A small hawk chained to another perch shook its jesses. The owl had the same amber eyes as its master. Ludo shifted from one foot to the other, not unlike the smaller bird then, aware of what he had done and how it might be interpreted, stood straight, folding his arms across his chest.

The sheik, an elderly man similar in appearance to the pearl trader in a flowing white robe and square-set head cloth, tapped his beak-like nose. It was flattened at the tip. As Ludo’s vision became more accustomed to the low indoor light, he tried to decide if the flattening were natural or the result of an accident or fight, then chastised himself for becoming distracted and wondered how the sheik might be reading his features: the newly-grown beard that still itched, his Indian cotton pyjamas, his swollen, reddened hands from helping on deck after a long period of living in comfort.

Breaking the tension, the sheik snapped his fingers and a servant brought in a tray of sherbet and sugary date and almond morsels. He then indicated a cushion and invited Ludo to sit at the low table covered in a cloth with yellow and gold, white and red squares. Appliquéd onto the squares were fat, winding snakes and unstable ladders that tilted up and across the cloth. Words and phrases had been embroidered into certain squares in black but Ludo couldn’t read them.

“It was brought to my father’s father or perhaps his father’s father, many years ago from India,” the sheik said. “It is called moksha patam.” He placed two ebony white-spotted dice on the middle of the cloth.

“Ah, it is a game, like parchis.”

“Yes and no. Parchis requires a certain skill; moksha patam depends to a greater degree on the fall of the dice – and an individual’s luck.”

“A game of chance.”

“More than mere chance, my friend: truly it is a study in karma and kama; destiny and desire. We shall play together.”

“For the horses? If I win, I may take them?”

“No.”

“Then forgive my bad manners, Excellency, but I have no time for games.”

The sheik handed Ludo the dice. “As a guest you may throw first.”

Ludo delayed his response, taking a sip of sherbet to hide his annoyance; he was not in the mood for mystical games of chance, time wasted here could put his ship in jeopardy. If Tulip’s pursuers found their hiding place and he was not aboard . . . Ludo closed his eyes, not wanting to complete the thought, and rattled the dice in his accommodating palm out of sheer habit.

The sheik pointed to a ladder. “The ladders take you up to the end of the cloth and finally, if you win, bring you to ‘salvation’. The snakes take you down through your earthly vices. Look,” he pointed at the words stitched into the cloth, “your first chance to rise is through ‘faith’, then ‘reliability’, ‘generosity’, ‘knowledge’ and ‘asceticism’. But you can be brought back down again by ‘disobedience’, ‘vanity’, ‘vulgarity’, ‘drunkenness’ and ‘debt’. The longest and therefore the worst of these snakes are these which bring you back or near to the beginning, meaning you must start your climb all over again: watch out for ‘rage’ and ‘greed’, ‘pride’, ‘murder’ and ‘lust’. This one fat serpent here crossing the entire cloth is ‘lying’ – telling that which is not true.”

“There are fewer ladders than snakes,” Ludo said.

“Such is life.”

Ludo jiggled the dice. “And there is no one ladder that can take you straight to the top; but this snake up here can take me right back to the beginning.”

“No one single virtue is sufficient for salvation. What good is generosity if you are unreliable and guilty of greed and self-love?”

Trapped, Ludo tried to relax and indicated he was ready to begin. It was after all, only a game, although as the sheik had pointed out, not exactly a game for once he had begun he couldn’t help but wish for more virtues and lament his vices. In parchis, with a bit of cunning and friendly dice you could win within an hour. Not so here.

Ludo lost, devoured by the serpent of ‘disobedience’ twice, then ‘greed’ when he was close to finishing. He wanted to blame the sheik, who had maintained his scrutiny of his guest throughout, unnerving Ludo each time he threw.

Glad that it was over, Ludo tried to pull on his old mask of bonhomie and said cheerily, “Is there a prize for you, Excellency?”

“Is salvation not a prize?”

“I doubt I will ever find out, Excellency. Where I come from there’s no point even trying. And as I am no Hindustani I do not have to worry about the Wheel of Re-incarnation.” Across the room, the eagle owl glowered.

“Neither am I of Hind my friend, but I do believe a better life is attainable while we are on God’s earth. Only a complete fool dismisses the possibility of returning – being condemned on the Wheel.” The sheik drank from his cup of sherbet and ate a sweetmeat, taking his time.

Ludo forced himself not to squirm, pondering whether the actions related to ‘whim’ should be classified as a vice. Then his blood ran cold: on a whim he had walked into a trap. He had made himself a prisoner while the sheik’s men were unloading his ship. Rapidly he cast about for a guard but saw only the owl and the hawk; wisdom and aggression.

“You are nervous my friend. You fear I shall not let you go. You fear we shall take your cargo. It is within our power, but I would have hoped this past hour had shown you we are aware of the penalty of greed. Not that we have no need of your cargo. Spices from India, silks and tea from Cathay? You have tasted our sweetmeats: cinnamon from Ceylon would be most welcome here. Perhaps on your next voyage you will allow me to purchase from you?”

“Gladly, Excellency.” Ludo endeavoured to keep relief from his voice.

*

The game Ludo is playing here (and his name, shortened from Ludovico, is no accident) is far more complex than our children’s ‘Ludo’ or parchis, but the combination of skill and luck remain the same. The original game was a tool or means for teaching the effects of good deeds versus bad. As in this scene, the ladders represented virtues such as generosity, faith, and humility, while the snakes represented vices of lust, anger, murder, and theft. The moral to be learned was that a person can attain salvation (moksha) through doing good: doing evil one will lead to re-birth. The number of ladders was less than the number of snakes as a reminder that the path to salvation is full of obstacles and should be trod with caution. There were fewer ladders than snakes; as the sheik here says, such is life. In the game he and Ludo are playing, the squares of virtue are faith (12), reliability (51), generosity (57), knowledge (76), and asceticism (78). The squares of vice or evil are disobedience (41), vanity (44), vulgarity (49), theft (52), lying (58), drunkenness (62), debt (69), rage (84), greed (92), pride (95), murder (73), and lust (99); number 100 was salvation.

Ludo leaves the sheik a somewhat confused man without the mares he wished to buy. In the rest of the story we see him climb numerous ladders both physical and metaphorical, only to slip back down the fat snakes of ‘disobedience’, ‘greed’ and even ‘theft’ until chance, skill and luck redeem him and take him where he had not planned to be: a place offering the peace and contentment he didn’t know he was seeking.

*(1)The image above and some information on the of snakes and ladders comes from: http://iseeindia.com/2011/09/11/the-origin-of-snakes-and-ladders (accessed 23rd April, 2018 @ 11:21)

The Chosen Man and A Turning Wind are available from book stores and on-line retailers. The Amazon UK link for books by J.G. Harlond is: https://www.amazon.co.uk/s/ref=nb_sb_noss?url=search-alias%3Daps&field-keywords=+j.g.+harlond&rh=i%3Aaps%2Ck%3A+j.g.+harlond&ajr=0

This post was originally written for Antoine Vanner’s Dawlish Chronicles Blog: https://dawlishchronicles.com

While researching events in Britain during 1944, I came across a short comment made by someone on a history blog about how Churchill and Eisenhower met for an ultra-secret meeting at a private home on the east coast of Scotland in the month prior to D-Day.

While researching events in Britain during 1944, I came across a short comment made by someone on a history blog about how Churchill and Eisenhower met for an ultra-secret meeting at a private home on the east coast of Scotland in the month prior to D-Day.

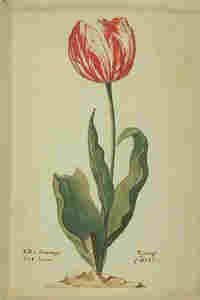

The first extract is from Book 1 of The Chosen Man Trilogy. It is 1635, charismatic Genoese merchant Ludovico da Portovenere (Ludo) is engaged in a conspiracy to inflate the tulip market in what became known as tulip fever. At this stage, readers are not sure whether Ludo is to be trusted, whether he’s a goodie or a baddie. How he handles his young Spanish servant Marcos here suggests he exploits people for his own ends. The dialogue also carries vital details about ‘tulipmania’.

The first extract is from Book 1 of The Chosen Man Trilogy. It is 1635, charismatic Genoese merchant Ludovico da Portovenere (Ludo) is engaged in a conspiracy to inflate the tulip market in what became known as tulip fever. At this stage, readers are not sure whether Ludo is to be trusted, whether he’s a goodie or a baddie. How he handles his young Spanish servant Marcos here suggests he exploits people for his own ends. The dialogue also carries vital details about ‘tulipmania’.

The sheik was seated on cushions in a high-ceilinged room. There were no intricate tiles such as those of the Arab homes Ludo knew in North Africa, only brightly coloured wall-hangings and mats, and on a low oblong table a large patchwork cloth.

The sheik was seated on cushions in a high-ceilinged room. There were no intricate tiles such as those of the Arab homes Ludo knew in North Africa, only brightly coloured wall-hangings and mats, and on a low oblong table a large patchwork cloth. There are two sets of Dorothy Dunnett’s two historical novel series on my bookshelves, plus two copies of King Hereafter: a few are hardbacks the rest are now dry, cracked-spine paperbacks, whose pages are so yellow and print so small that I struggle to read them – but I still do. I’ve bought a few replacements over the past forty years, but somehow can’t bring myself to throw or even give away the originals. The other curious thing about these old books is something very modern. Without strapping any box to my head or standing in any man-made cubicle wearing black goggles they produce a form of virtual reality. Just by looking at a title I can see scenes. Stills and moving images hang in the air: a joyous youth riding an ostrich, the same man now older rides a silken-hide camel; a little boy with sturdy legs runs through apricots drying on a rooftop; a vast eagle swoops across a snowy waste onto an arm; a mad, brave youth runs across moving oars and marries a woman with ‘spawn-like’ eyes . . .

There are two sets of Dorothy Dunnett’s two historical novel series on my bookshelves, plus two copies of King Hereafter: a few are hardbacks the rest are now dry, cracked-spine paperbacks, whose pages are so yellow and print so small that I struggle to read them – but I still do. I’ve bought a few replacements over the past forty years, but somehow can’t bring myself to throw or even give away the originals. The other curious thing about these old books is something very modern. Without strapping any box to my head or standing in any man-made cubicle wearing black goggles they produce a form of virtual reality. Just by looking at a title I can see scenes. Stills and moving images hang in the air: a joyous youth riding an ostrich, the same man now older rides a silken-hide camel; a little boy with sturdy legs runs through apricots drying on a rooftop; a vast eagle swoops across a snowy waste onto an arm; a mad, brave youth runs across moving oars and marries a woman with ‘spawn-like’ eyes . . . If you recognise any of these scenes you probably qualify as a Dorothy Dunnett fan, and are very likely a ‘historical fiction junkie’. That’s what I was told Dunnett fans were a few years ago. There are currently three Facebook groups for Dunnett fans that I know of. I dip in now and again and am always rewarded by some insight into a bit of history or details on one of the many locations. The news on one today is from a student in Australia who is writing her MA dissertation on Dunnett.

If you recognise any of these scenes you probably qualify as a Dorothy Dunnett fan, and are very likely a ‘historical fiction junkie’. That’s what I was told Dunnett fans were a few years ago. There are currently three Facebook groups for Dunnett fans that I know of. I dip in now and again and am always rewarded by some insight into a bit of history or details on one of the many locations. The news on one today is from a student in Australia who is writing her MA dissertation on Dunnett.