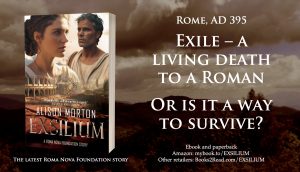

Exile – the only way to surive

There is an excellent new addition to Alison Morton’s fascinating series Roma Nova, which tells the story of three very different people forced into exile by events in 4th Century Rome.

As I was reading, I became aware through small details that Alison Morton probably knows everything there is to know about 4th Century A.D. Rome and Romans. This knowledge deepens the story a great deal because what happens to the three main protagonists is a result of contemporary circumstances. Circumstances that resonate in our 21st Century. It is surprising, and not a little disquieting, how much our lives have not changed. Religious intolerance, gender issues, family ties and tensions, they are all here, plus the sad need to find a new place to live, and the difficulties and dangers involved in getting there.

I became invested in the main characters and found myself thinking about them between readings: Lucius Apulius, an ex-tribune, Galla Apulia, his eldest daughter, and Maelia Mitela, widow of a man labelled as a pagan traitor for holding on to belief in the ancient gods; each struggle with personal traumas along with the difficulties of a society at a critical point of change. Morton develops her characters in such a way that one can see why they make certain choices, and how they change during the course of the story.

Details of everyday life such as food and clothing, household management and social expectations enrich the story. Action scenes, where the outcome is never obvious, also kept me turning pages. Quality reading for Roman history buffs and hist-fic fans alike. © J.G. Harlond

Buying links: Amazon: https://mybook.to/EXSILIUM

Other retailers: https://books2read.com/EXSILIUM

About the author:

Alison Morton writes award-winning thrillers featuring tough but compassionate heroines. Her ten-book Roma Nova series is set in an imaginary European country where a remnant of the Roman Empire has survived into the 21st century and is ruled by women who face conspiracy, revolution and heartache but use a sharp line in dialogue. The latest, EXSILIUM, plunges us back to the late 4th century, to the very foundation of Roma Nova.

She blends her fascination for Ancient Rome with six years’ military service and a life of reading crime, historical and thriller fiction. On the way, she collected a BA in modern languages and an MA in history. Alison now lives in Poitou in France, the home of Mélisende, the heroine of her two contemporary thrillers, Double Identity and Double Pursuit.

Social media links

Connect with Alison on her thriller site: https://alison-morton.com

Facebook author page: https://www.facebook.com/AlisonMortonAuthor

X/Twitter: https://twitter.com/alison_morton @alison_morton

Alison’s writing blog: https://alisonmortonauthor.com

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/alisonmortonauthor/

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/5783095.Alison_Morton

Threads: https://www.threads.net/@alisonmortonauthor

Alison’s Amazon page: https://Author.to/AlisonMortonAmazon

Newsletter sign-up: https://www.alison-morton.com/newsletter/

The cover and title of this novel are worth thinking about before one opens the book itself. The author is telling us that at one level it is historical fiction, a tale told about a past epoch and how people lived then; at another, it is a story of someone’s life but not a biography. It is a story: the author’s interpretation of what happened to Nellie Bly. Who in turn was not only Nellie Bly but Elizabeth Cochrane, a young woman shaped by the lamentable circumstances of her parents’ life – which she is determined to overcome. The puzzle starts here, but is quickly forgotten because the author’s lucid prose and excellent characterisation means that one falls into the events of Nellie Bly’s life as if they were happening for the first time now.

The cover and title of this novel are worth thinking about before one opens the book itself. The author is telling us that at one level it is historical fiction, a tale told about a past epoch and how people lived then; at another, it is a story of someone’s life but not a biography. It is a story: the author’s interpretation of what happened to Nellie Bly. Who in turn was not only Nellie Bly but Elizabeth Cochrane, a young woman shaped by the lamentable circumstances of her parents’ life – which she is determined to overcome. The puzzle starts here, but is quickly forgotten because the author’s lucid prose and excellent characterisation means that one falls into the events of Nellie Bly’s life as if they were happening for the first time now. In the year 1490, Brother Jacomo of Seville is sent to Brabant as a Papal Inquisitor. He loses no time in condemning a man to be burned alive in the main square of Den Bosch. It is a public warning: be sure your sins will find you out.

In the year 1490, Brother Jacomo of Seville is sent to Brabant as a Papal Inquisitor. He loses no time in condemning a man to be burned alive in the main square of Den Bosch. It is a public warning: be sure your sins will find you out.