The new Bob Robbins Home Front Mystery

A new Bob Robbins Home Front Mystery was released this month. If there is such a thing as a ‘historical country house murder mystery thriller’, Secret Meetings falls into that genre.

This story, like the others in the series, is based on real events during the Second World War. In this case, it is the secrecy and misinformation related to what became known as D-Day, the Allied counter invasion of France in 1944.

During the preparations for the 1944 Normandy landings known as Operation Overlord then D-Day, a parallel wartime strategy was taking place in the United Kingdom aided by the terrific bravery of British agents in Germany itself: Operation Bodyguard. This was an act of subterfuge designed to mislead Hitler into thinking the counter-invasion would come via Norway and the Pas-de-Calais. We know about this today as Operations Fortitude and Fortitude South; all of which was supposedly top secret but deliberately leaked into Germany right up to 1945. The success of this was down to keeping what was happening on the south and south west coast of Britain absolutely secret.

D-Day was co-ordinated from General Eisenhower’s headquarters in Portsmouth. Allied craft initially landed 156,000 American, British and Canadian forces on five beaches codenamed Gold, Juno, Sword, Utah, Omaha, along a 50-mile stretch of heavily fortified French coast on June 6, 1944. It was a major turning point in the Second World War.

While researching events in Britain during 1944, I came across a short comment made by someone on a history blog about how Churchill and Eisenhower met for an ultra-secret meeting at a private home on the east coast of Scotland in the month prior to D-Day.

While researching events in Britain during 1944, I came across a short comment made by someone on a history blog about how Churchill and Eisenhower met for an ultra-secret meeting at a private home on the east coast of Scotland in the month prior to D-Day.

This meeting was not only kept secret from the press, other Allied leaders and politicians knew nothing about it. So how did these two men, and Winston Churchill in particular, disappear from public view for over 24 hours at such a crucial time? Answer: a decoy trip to the other end of the country was leaked to the daily press. Enter dumpy, grumpy Bob Robbins, and a small brown poodle.

The setting for the story – the country house – came to me while I was looking for accommodation in North Devon online a couple of years ago. Up popped a photo of a country house hotel, where I had spent a tedious student summer washing dishes and trying to avoid the ill-tempered owner. The sprawling, gloomy Victorian house in its attractive riverside setting was just right for my story. What had felt like a tremendous waste of my time all those years ago suddenly became very worthwhile.

After this, I discovered a key point to the plot of the story while listening to a Second World War reconnaissance pilot talking about the perils of low altitude flying over France in daylight. And this is how the wicked crime at the centre of the story links a country house murder committed in a Cornish backwater to international events. There’s no escaping world events in wartime.

As you may know, my stories are all based on real events, and take place in two different centuries, but there is also a common location running through the list, the English West Country, where I grew up. With very few exceptions, wherever the action occurs, be it Amsterdam, corsair-stronghold Ibiza, or Bodmin Moor, I have spent time there in the past, and I am there as I write. The plot may be largely fictitious or more closely based on a real event, but the location is always real. Having said that, I often fictionalise West Country place names to avoid irate readers telling me such and such an alley doesn’t exist, or the house on the river was built of brick not local stone. This has happened.

In my 17th century novels, The Chosen Man Trilogy, Ludo da Portovenere, a Genoese merchant, secret agent, part-time pirate and full-time rogue, gets up to no good on behalf of the Vatican and European monarchs. The espionage and some of the crimes actually happened, but Ludo’s travels depend almost entirely on my own. In The Bob Robbins Home Front Mystery series (set in WWII Devon and Cornwall) the crimes may seem home grown, but they are each linked to what was happening in the wider world.

As an author I try to help readers escape everyday chores for a few hours. If you enjoy action/adventure and espionage, check out The Chosen Man stories and/or The Empress Emerald.

For more fiction like this take a look at my ‘good read’ recommendations on http://www.shepherdbooks.com. This is a great new place to find the sort of books you like reading: The best historical fiction to take you travelling across Europe (shepherd.com)

And if, after reading Secret Meetings you are curious to know more about the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, I recommend That Woman: The Life of Wallis Simpson, Duchess of Windsor by Anne Sebba.

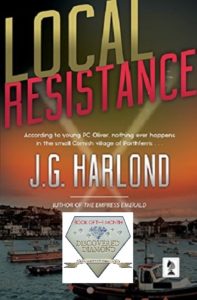

Secret Meetings can be read as a stand-alone, but if you’d like to start the Bob Robbins Home Front Mystery series from Book 1, begin with Local Resistance. It is available on all book platforms and as an audio book. http://getbook.at/LocalResistance

The Chosen Man Trilogy is published by Penmore Press and available on all online retailers and in book shops.

Bob Robbins Home Front Mysteries are also available on Amazon Unlimited.

Local Resistance is available as an audio book.

Web page: https://www.jgharlond.com

Find me on Twitter: @JaneGHarlond

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/JaneGHarlond

From my desk here in the Province of Málaga I can see the Sierra de Las Nieves. This was where the Moors of Al-Ándalus used to harvest snow to be collected in summer for sherbet and to keep medicines cool. To the right out of a large picture window is the bandalero country of The Empress Emerald; to the left, beyond mauve-shaded mountains, are ancient fishing villages now known as the Costa del Sol, but once prey to the Barbary corsairs featured in The Chosen Man Trilogy.

From my desk here in the Province of Málaga I can see the Sierra de Las Nieves. This was where the Moors of Al-Ándalus used to harvest snow to be collected in summer for sherbet and to keep medicines cool. To the right out of a large picture window is the bandalero country of The Empress Emerald; to the left, beyond mauve-shaded mountains, are ancient fishing villages now known as the Costa del Sol, but once prey to the Barbary corsairs featured in The Chosen Man Trilogy.

Despite my somewhat Latinized outlook, though, what I see through my Spanish picture window when I am at my desk in Málaga is still with a realistic Englishwoman’s eyes.

Despite my somewhat Latinized outlook, though, what I see through my Spanish picture window when I am at my desk in Málaga is still with a realistic Englishwoman’s eyes. If, like me, you enjoy novels that takes you into the past and/or far away, check out the excellent Bristish historical fiction author, Deborah Swift. She has a new novel set in 17th century Italy out now, too.

If, like me, you enjoy novels that takes you into the past and/or far away, check out the excellent Bristish historical fiction author, Deborah Swift. She has a new novel set in 17th century Italy out now, too. If you enjoy gritty, contemporary British police crime fiction, try B.A. Morton’s frightening, heart-rending ‘Crime on the Tyne’.

If you enjoy gritty, contemporary British police crime fiction, try B.A. Morton’s frightening, heart-rending ‘Crime on the Tyne’.

In Britain and Ireland, there was the added, critical risk of imminent invasion. It had happened in Poland and the Channel Islands, it could happen in Britain. The detail about the German U-boat surfacing off the Cornish coast to take on fresh water in Local Resistance was taken from a German sailor’s account. I didn’t invent that.

In Britain and Ireland, there was the added, critical risk of imminent invasion. It had happened in Poland and the Channel Islands, it could happen in Britain. The detail about the German U-boat surfacing off the Cornish coast to take on fresh water in Local Resistance was taken from a German sailor’s account. I didn’t invent that. How a Cornish fishing village uses its ancient smuggling tradition to evade rationing while preparing to defend their country when ‘Jerry’ landed forms the background to Local Resistance; how people as diverse as Land Army girls and cosmopolitan actors coped three years into the war underlies the shenanigans and criminal activities in Private Lives.

How a Cornish fishing village uses its ancient smuggling tradition to evade rationing while preparing to defend their country when ‘Jerry’ landed forms the background to Local Resistance; how people as diverse as Land Army girls and cosmopolitan actors coped three years into the war underlies the shenanigans and criminal activities in Private Lives.  It is 80 years now since Daphne du Maurier’s novel Rebecca was first released. Back in 1938, du Maurier’s publishers were nervous about the novel’s future, but the story has become a classic: a world-wide favourite, a play, a television series, even an iconic black and white movie. For a while, back in the 90s, new editions of du Maurier’s novels were hard to obtain, but with the recent film version of My Cousin Rachel she is very much back in the public eye.

It is 80 years now since Daphne du Maurier’s novel Rebecca was first released. Back in 1938, du Maurier’s publishers were nervous about the novel’s future, but the story has become a classic: a world-wide favourite, a play, a television series, even an iconic black and white movie. For a while, back in the 90s, new editions of du Maurier’s novels were hard to obtain, but with the recent film version of My Cousin Rachel she is very much back in the public eye. Big houses, full of private tragedies and secret histories, feature in many of her novels. Looking at photographs of Menabilly I wonder if that house stands as a metaphor for her fiction – as full of conflicting emotions, versions of the past and fantasies as the house on the strand. Such thoughts and ideas are only suggested, it is up to each reader to interpret them of course, and as in real life we interpret them according to our own way of thinking and personal experiences. Readers bring their own baggage to any book.

Big houses, full of private tragedies and secret histories, feature in many of her novels. Looking at photographs of Menabilly I wonder if that house stands as a metaphor for her fiction – as full of conflicting emotions, versions of the past and fantasies as the house on the strand. Such thoughts and ideas are only suggested, it is up to each reader to interpret them of course, and as in real life we interpret them according to our own way of thinking and personal experiences. Readers bring their own baggage to any book. This post first appeared in the Discovering Diamonds blog:

This post first appeared in the Discovering Diamonds blog: