The first recorded economic bubble, ‘tulipomania’, occurred in the Dutch United Provinces between 1635 and 1637. The 1630s were a period of intense political and religious intrigue, when Pope Urban VIII appeared to be supporting Spain’s attempt to reclaim her lost territories in the Netherlands, but was actually conspiring to limit the size and power of the Habsburg Empire, to which Spain belonged; when France was playing both sides against the middle to undermine Spain’s power in Europe; and ordinary men and women everywhere were dying of the plague.

Set during this epoch, my novel The Chosen Man features the charismatic, wicked but likeable Ludovico da Portovenere, a charming Genoese rogue known to everyone as Ludo, and shows how it can take just one man with the right connections to create financial mayhem and ruin the lives of humble men and women. Acting on behalf of the Spanish monarch and Vatican cardinals, Ludo encourages and facilitates the futures market and outrageous sales of tulip bulbs in Holland. However, while I may have tinkered with fact in this area, the very real presence of the plague in the United Provinces at the time must have played a critical part in what actually happened.

Set during this epoch, my novel The Chosen Man features the charismatic, wicked but likeable Ludovico da Portovenere, a charming Genoese rogue known to everyone as Ludo, and shows how it can take just one man with the right connections to create financial mayhem and ruin the lives of humble men and women. Acting on behalf of the Spanish monarch and Vatican cardinals, Ludo encourages and facilitates the futures market and outrageous sales of tulip bulbs in Holland. However, while I may have tinkered with fact in this area, the very real presence of the plague in the United Provinces at the time must have played a critical part in what actually happened.

The conspiracy theory behind what Ludo does in the novel has never been proved, and I should point out that Ludo is a fictional character, but the tulip bubble is documented history. Contemporary reports and records of sales transactions demonstrate the outrageous escalating prices paid up to 1637, when the bubble burst. The question is why did otherwise sober, thrifty Dutchmen, and many women, engage in what was basically gambling – with flowers that for most of the year could not even be seen? The answer lies in the combination of factors, but the very present threat of the plague, I think, was the final impetus. Death was literally on their doorsteps.

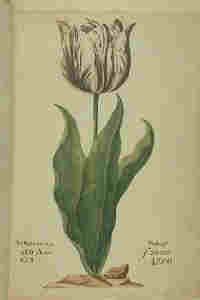

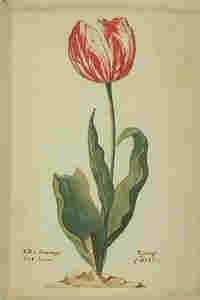

Let us take Amsterdam in 1635 as an example. It’s a busy, thriving city with a huge population for the epoch. The Dutch have wrested their independence from Spain and are currently engaged in the Thirty Years War in Flanders to keep it. The general ethos is what we now call the ‘work ethic’; frippery and ostentation are frowned upon. So what can people who by their very thrift have acquired surplus income spend their money on? Something that is not an adornment or a visible luxury, but is defined as a ‘connoisseur item’ and coveted; something that is guaranteed to double, triple its value in the space of a year, a month, a week . . . Tulip bulbs. Money must not lie idle.

But does this really explain why people are willing, desperate even to spend their savings and then raise cash or exchange their worldly goods for flowers? Not altogether. I think the bell they hear each evening and the cry ‘Bring out your dead’ is probably the final motivating factor. Many if not most of the people engaged in this futures market are Protestants and Calvinists: they must work hard and be seen to work hard to earn their passage to heaven and be counted among the ‘elect’ – but they could be dead tomorrow. Their future is as shaky as the anticipated profits in tulip transactions – so what is there to lose? And if in the process of buying and selling on little brown bulbs they make even more money, their families will be provided for in the future.

An industrious author of the time, Munting, wrote over a thousand pages on ‘tulipomania’. In one pamphlet he recorded the items and their value which were traded for a single Viceroy bulb (see illustration). As you read, bear in mind the family of a shoemaker or baker lived on between 250 and 350 guilders a year.

| Item | Value (florins) |

| Two lasts of wheat | 448 |

| Four lasts of rye | 558 |

| Four fat oxen | 480 |

| Eight fat swine | 240 |

| Twelve fat sheep | 120 |

| Two hogsheads of wine | 70 |

| Four casks of beer | 32 |

| Two tons of butter | 192 |

| A complete bed | 100 |

| A suit of clothes | 80 |

| A silver drinking cup | 60 |

| Total | 2,500 |

At its height, in the early spring of 1637, a Dutch merchant paid 6,650 guilders for a dozen tulip bulbs. The merchant wasn’t simply a rich man buying expensive the bulbs to plant and enjoy for their colour, he intended to sell on and make a profit – as his fellow Dutchmen had been doing for the past two years. Records document instances of farmers giving up their farms to acquire bulbs and men exchanging their homes for a just one single rare bulb. Artisans pawned or sold their tools to ‘invest’ in tulips. Between 1635 and 1637 everyone, it seemed, was trading in tulips. There were also connoisseurs, mostly belonging to the professional class, who spent huge sums on what they considered an object of art. All these people, merchants, artisans and lawyers, fell prey to this collective madness – why?

As I say, there is no single answer, but the socio-economic and climate conditions of the epoch were perfect for ‘tulip mania’. Having lived in the province of Holland I can fully appreciate why, once tulips had been introduced into northern Europe at the turn of the 17th century, they became so popular. Tulips bring colour and a promise of spring at the end of long, dark, tedious winters. The 1600s were during a mini-ice-age: no wonder people wanted something to brighten their homes and gardens. This was also the period known as the Dutch ‘golden age’. The Protestant ethic of hard work and the egalitarian nature of the Independent Provinces meant many people now had a disposable income. It was a period of house-building and home-improvements; people were buying musical instruments and investing in works of art. But the plague was everywhere: death was quite literally round the corner. Dutch frugality and diligence had led to wealth, but many obviously feared they might not have the time to enjoy it and took to the excitement and risks in gambling.

Here is an extract from The Chosen Man that illustrates the situation in Amsterdam in 1636. Encouraged by the wicked Ludo da Portovenere, Elsa vander Woude, a wealthy widow, has become involved in tulip trading. The scene takes place in her salon:

. . . the unspoken promises she believed had urged her into buying and selling on a scale she could never have imagined. Just this week she had speculated on a whole bed of bizarden tulips owned by a Haarlem florist. And her enthusiasm, her physical drive had impelled Paul Henning into the speculator’s market, too. He was already trading on the bulbs just in the ground and not to be lifted until after they bloomed in March, April or May. It was gambling, of course, and that had held him back at first, but he was as much a part of the new tulip trade as she was now, and making an excellent living. Good Paul Henning with a proper bank account; a fine, safe account in one of the new Amsterdam banks. (. . . ) And here he was mixing as an equal in his late employer’s salon with his wife and other gentlemen and their wives, all enjoying fruit punch and sweet wine, and celebrating a good year’s trading. Such changes! Such good changes bringing benefit to all. Elsa turned her back to the window and sought out her late husband’s loyal clerk.

Paul Henning was not mingling as she imagined, he was standing at the far side of the room observing what was going on around him, a very serious look on his face. Stopping for a polite word here and there, Elsa crossed the room to stand beside him. “Henning, my dear, why so glum?”

“Glum? No, not glum, Me’vrouw.”

“Then what are you thinking? Dark thoughts I fear, but I cannot see why.”

“Forgive me. I feel a little out of place here. I was not raised to mix with the rich.”

“Neither you, nor many here (. . .) Tulips are a great leveller Henning. Don’t feel ill at ease (. . .) You’re going to be a rich man Henning. It’s so much easier now we don’t actually have to have the bulbs in our hands to sell them. Do you know, last week I sold a whole bed of tulips—the ones I bought near Haarlem last spring for—well, for an awful lot more than I paid, and they were already in the ground. The whole transaction took two pieces of paper. It wouldn’t surprise me if that same bed of flowers doesn’t get passed on at a tremendous profit four, five times before spring!”

“That’s what worries me, Me’vrouw. To be honest, it is exactly that which worries me. If you—we—are buying and selling without seeing the product—well, anyone can cheat us. Tell us they’ve got a bed of purple on white and when they’re lifted they’re just plain red or yellow. And buying bulbs and off-sets according to goldsmiths’ weights doesn’t seem to make much sense either. Since when was a big winter potato any better quality than a small, floury summer root? Something here is not right, Me’vrouw.”

“Oh, you Doubting Thomas! You Jonah!” Bending her head to the concerned man Elsa whispered, “Does it matter? I mean we’ve got some lovely flowers already, we know they are safe and right; what harm can a little speculating do?”

Paul Henning did not reply. Then quietly he said, “Me’vrouw, I was raised to understand that the respectable working man worked hard to keep his place. What I fear is not that I will fail to get rich, but that I will lose what little I have. Security is all. If you will forgive me saying, it was your late husband’s motto, was it not?”

Elsa did not reply; she was not listening. Paul Henning smiled cautiously and Elsa vander Woude went on spinning an elaborate future for his family.

Above the hum of voices and laughter there was the distant clanging of the plague bell and the terribly familiar call, “Bring out your dead.”

“Death is also a great leveller,” Paul Henning murmured.

Both Elsa and Paul Henning will suffer when the bubble bursts although they are involved in tulip trading for very different reasons: Elsa because she wants to believe in Ludo; and Henning because he has a family and no other income. Each has a very different outlook on life, but ultimately they are both victims.

The initial idea for the main plot in The Chosen Man came to me while watching a documentary about the fall of Lehman Brothers. There are clear parallels also to the mortgage scandals in Britain and the USA of recent years; how people had been encouraged to borrow well above their means believing the market would only ever be buoyant; and how, in some cases, it took just one man to set in motion a dramatic financial collapse. Obviously, we are not threatened by the plague but in many ways life today is just as precarious: car crashes, plane crashes, heart-attacks . . . People rarely learn from history – but . . . Carpe Diem.

Hey! Someone in my Myspacе group shared this site with us so I came to take a look.

I’m definitely loving the information. I’m bookmarking and

will be tweеting this to my follⲟwers! Exceptiⲟnal blog and superb style and design.

Thank you for commenting, Karolin. The 17th century in Europe must have been a very dangerous time, what with persistent wars, plague and the mere everyday struggle to survive, whether one was wealthy or not. Makes for great fiction, of course.